This discussion of why we should and do search and research may appear circuitous, but it is part of the biological need for self-preservation, which directs a drive for food. The other, oriented toward species preservation, is activated during the metamorphosis of puberty and channels the drive for sex.

The group of nerve cells involved in the search for food may function as a “glucostat,” somehow becoming active when their glucose level falls below a certain critical amount. Their impulses direct complex neuromuscular mechanisms to obtain food, digest it, and distribute it “to all parts of the body for nourishment” (as Galen said nearly two millennia ago). When the cell glucose rises to the critical level, the “glucostat” shuts off, and the cells in the food-intake center become quiescent. A nearby group of food-satisfaction cells, working in opposition to the food-intake center, elicits feelings of comfort, satiation, and well-being.

The feeling of satisfaction after a good meal, functioning in a primitive form in fishes and lower vertebrates, can be conditioned, as Russian physiologists enjoy demonstrating. In higher vertebrates, including ourselves, this feeling, so critical for our activity and welfare, begins to be conditioned from the first meal at our mother’s breast. The snug sense of warmth, comfort, security, and well-being, neatly summarized in the word “satisfaction,” is deeply imprinted, and we learn quickly to search and research for it.

Here, then, is a basic biological answer to our question, why search and research: it is because we seek satisfaction through whatever conditional reflex produces this sensation. Even beneath the highly sophisticated methodology of scientific research, the goal of personal satisfaction through achievement remains paramount, no matter how we may try to disguise it as status or other symbols of prestige.

The group of brain-stem cells that regulate the drive for sex may be governed by a different chemostat—one dependent on the internal metabolic build-up of a variety of polarizable amines, such as 5-hydroxytryptamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, histamine, and many others, even including ammonia. All of these, by influencing ion migration in relation to cell surfaces, may gradually develop a “charge” on the cells. Here popular and scientific language coincide!

The accumulating charge in the limbic system cells associated with species preservation activates a great complex of neuromuscular-sensory feedback mechanisms. Mental, muscular, visceral, and autonomic tensions mount until “discharge” creates an orgasm. After the accumulated amines spill out of the cell, as can be deduced from the effects of “quieting” drugs such as reserpine, the cells “depolarize” and become quiescent. The individual relaxes, feeling comfortable, successful, and, in short, satisfied.

Here again, we humans are susceptible to extensive conditioning. Although we may sublimate this sense of satisfaction intellectually, emotionally, or physically, the cycle of subconscious search and research for its achievement continues. The curiosity that is the basis for our endeavors to search and research is more than free-wheeling intelligence: it seems to be part of the unconscious neurochemistry and physiology of our hypothalamus and limbic system, rooted in the biological drives for individual and species survival. Parents and social forces, through our hopes of reward or fears of punishment, teach us the broad satisfactions possible from our search and research in living—whether reflected in the simple curiosities of children or in the sophisticated investigations of scientists.

Interrelations of Purposes, Knowledge, and Judgment

Differences in conditioning account for the variety of satisfactions sought by diverse individuals. While our primary purpose in living is to satisfy our own needs, we learned long ago that each individual must adjust his goals to those of other individuals. Motives must be examined, and interpersonal relations must be studied. Aristotle and the other ancient Greek philosophers grouped these matters into the general problem of ethics: how to achieve satisfaction; how to be happy; how to live the good life; what is “goodness”? The answers suggested over the centuries of our conscious history comprise the various ethics.

The dichotomy between the two chief ethical theories—hedonism, or the principle of human activity based on individual personal pleasure, and Platonic idealism, or the principle of voluntary individual sacrifice for the benefit of social welfare—indicates that the Greeks recognized the distinction between the biological levels of individual and social existence. These conflicting positions are difficult to reconcile. It is remarkable, however, that Platonic idealism is often religiously acceptable to those who repudiate it politically. Aristotle himself favored harmonious adjustments between people for the common good of all.

Of fundamental significance was the early realization that whatever one’s purpose in living, it would be more satisfying if one possessed substantial knowledge about oneself and one’s surroundings. Here is curiosity again: the basic drive to know the “truth” about ourselves and our environment in order to obtain satisfaction.

Determining the “truth” about ourselves and our world, and the best means of seeking it, constitute the problem that the various logics attempt to solve. By his skillful analysis of the process of reasoning, Aristotle developed a deductive logic, reflected in Euclid, which dominated thinking in the Middle Ages. If certain assumptions were granted, it was possible to deduce a magnificent body of faith, not to be questioned until new logics were discovered, such as the inductive method popularized by Francis Bacon. We are now exploring various symbolic and other logics.

Meanwhile, from gradual agreement on anthropomorphic standards of measurement, making possible the verifiability of observation and experiment by independent investigators, the concept of “science” in relation to truth developed. With this concept, the “truth” about ourselves and our environment has been freed from the demon “ideal of an absolute” to which mere approximations are possible. The “truth” is seen to be relative, subject to modification as new observations are made.

Scientific effort, to establish “true knowledge” about ourselves and our environment, has been quite successful in giving us the basis for getting many satisfactions through our conditional searches. Science has contributed to social welfare and has brought individual satisfactions to many, yet two-thirds of the world’s people cannot satisfy their basic biological drive for food. We have greatly increased life expectancy without making the living more worth the while. We have created population pressures that breed tensions and violence. We dangerously pollute our air and water. Our very scientific success gives us the power to destroy both ourselves and the environment from which we evolved.

What is wrong? Again, the ancient Greeks had a word for it. They recognized that wise judgment is essential to apply knowledge to the accomplishment of purposes. Verifiable knowledge is an advantage not only for itself but also for guiding the choice of attainable objectives to accomplish individual or social purposes. The ancient Greeks answered this problem of judgment with the various esthetics. Beauty to them was fitness, appropriateness, in itself satisfying. They saw an inherent unity in truth, goodness, and beauty. Even to us, the points of view embraced in the logics, ethics, and esthetics can still have real meaning.

Part of the trouble is that we have condensed the stable triad of the logics, ethics, and esthetics into a dyad in an attempt to balance our sciences with our humanities. We tend to neglect consideration of our purposes. Our predicament may be illustrated by our health professions, especially medicine, which is often referred to as both a science and an art. The scientific part of medicine consists of the verifiable information we have about ourselves in health and in disease; the art of medical practice consists of applying this knowledge to the promotion of health in an individual patient confronting an individual physician, or in promoting mental and physical health in communities by appropriate public health measures. By implication, the purposes are clear—to promote health—but too often they are glibly dismissed. In our medical endeavor, as in most of our frantic living, we fail to give as detailed consideration to our purposes as we do to our sciences, or even to the goals of our arts and humanities.

Ours is an age of scientific predominance. The consequences of such imbalance are apparent everywhere: in population pressures with their resulting frustrations and in the despoilation of our world. Nevertheless, the unremitting search and research for the “truth” about ourselves and our interlocked environment may in itself give us the verifiable knowledge which we may learn to apply with increasing effectiveness to the increasing satisfactions of all.

Years ago, some of us amused ourselves one happy afternoon in the California redwoods by experimenting with the idea of deriving a scientific basis for an ethic. In the approved scientific method, we sought a descriptive, naturally operating principle governing the relationships between individuals or between groups of people—a principle operating whether we would be aware of it or not, or whether we would like it or not. From the plethora of human experience, we induced such a principle: “the probability of survival of a relationship between individuals or groups of individuals increases with the extent to which the relationship is mutually satisfying.” This was formulated long before we realized that there might be an evolutionary built-in neurochemical mechanism for satisfactions. This statement is, one may note, a reflection of Aristotle’s harmony ethic.

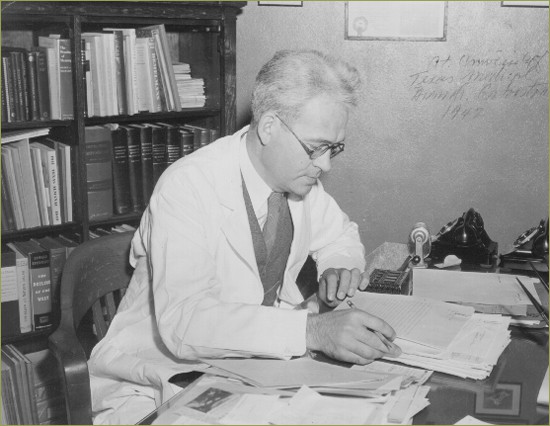

It would seem then that scientific effort might properly begin to encompass both ethics and esthetics. We need to know, verifiably, the determinants for purposes, conduct, and interpersonal relations on the one hand, as well as for factors in judgment and application of knowledge on the other. Quite appropriately, then, the AMA is asserting its voluntary intellectual leadership in health affairs by establishing an Institute for Biomedical Research. Again, quite appropriately, it is starting this highly significant venture at the basic level of molecular biology. Hopefully, it will progress to a systematic search for understanding of the interrelated structural and functional processes underlying health at all levels of biological organization.

It is pertinent to ask how search and research in molecular biology, at the very base of energy interchange between the chemical components of living material, promise anything of practical value to assist physicians whose purpose is solving the everyday problems of caring for sick people. This is another way of asking, why biomedical search and research? An answer may emerge from a consideration of the continuum of structural levels of living material.

The Significance of Organizational Levels of Living Material

Emerging cultures have always recognized the two obvious levels of biological organization—the individual organism and the social moiety. Familial and tribal societies conditioned all persons from infancy and through puberty rites to subordinate themselves to group welfare. In medicine, the Hippocratic school of the 5th century BC, with its background in Egyptian empiricism, was aware of the significance of this situation. Although most of the writings concern the management of sick persons, there is also recognition of the social level of human organization in such writings as Epidemics, Airs, Waters and Places, or Oath, Law, Decorum and Precepts.

Long ago, however, levels of organization of living material began to be appreciated beyond the individual or social phases. Pathological observations at sacrifices or postmortem examinations focused attention on organs. The clear demonstrations of Morgagni in the 18th century established the importance of organs in individual health and disease, and Bichat soon added tissues. Then in the 19th century came the dramatic expression by Schleiden and Schwann of cells as “units of living things.” Virchow in 1847 gave voice to the significance of organizational levels of living material by announcing his determination to establish pathology as a science concerned with disease from “cells to societies.” We still have little scientific understanding of social pathology, although Virchow brilliantly succeeded in conventionalizing cellular pathology.

Recently we have become aware of extensions at both ends of this continuum. Cells are now realized to be amazingly complex homeostatic devices consisting of many structural organelles such as nuclei, nucleoli, chromosomes, membranes, mitochondria, micro- and ribosomes, Golgi apparati, lipoprotein granules, and a flood of ions, enzymes, clathrates, chelations, organic complexes, and water matrices—all in a continual swishing swirl of inter-reacting movement, glimpsed in time-lapse movies of cellular or tissue cultures.

The genesis of cellular structure and function is now understood to reside in the complex macromolecules of ribose- and deoxyribose nucleic acids, with their chains of specifically arranged amino acids, which are the templates for protein synthesis, the carriers and transmitters of this coded information for life. In the form of genes and viruses, they are on the razor edge between living and non-living. Some are crystallizable yet capable of reproduction and metabolism under favorable conditions. Here is the fascinating, newly discovered jungle of molecular biology, the exploration of which may yield a basic understanding of the processes underlying the health or disease of cells, organs, and tissues, individuals, and societies.

Perhaps at the molecular level of biological organization, we can learn something about the complex integrating mechanisms that maintain the internal steady state of living material glimpsed by Claude Bernard and extended so well to the homeostasis of mammalian individuals by Cannon. This knowledge will surely come from our increasing basic understanding of the energy exchanges possible at submolecular levels, inherent in the very nature of matter.

Here is the reason for choosing molecular biology as the beginning effort of the Institute for Biomedical Research. This is a major social endeavor undertaken by the AMA, through its Education and Research Foundation, in fulfilling its avowed social responsibility to improve continually the standards of medical practice. The knowledge thus gained, if wisely applied by physicians of the future, may greatly contribute to the successful management and prevention of disease and to the promotion of good health in individuals and their communities.

At the far end of the continuum of living material, we have gone beyond societies, with a dramatic suddenness sparked by Rachel Carson, to comprehend the ecological structures from which we have evolved and which our strange new synthetic, gadgetized world is rapidly destroying to accommodate our terrifying numbers.

In this broad range of continuity of biological organization, the human being remains paramount in medical interest and in the practical business of treating and preventing pain and disease, and in promoting optimum individual mental and physical health. Molecular biology is the current fad in basic biomedical search and research. While it will tell us much scientifically about the fundamental chemical interaction between molecules in our cells which determine health or disease, it will not give us the judgment necessary to apply this detailed knowledge wisely and well for the benefit of whole individuals confronting us, sick or healthy. Judgment remains the essence of the art of medicine, to be acquired painfully only by long experience and careful comparisons with standards and ideals, as the Hippocratic physicians realized long ago.

New Opportunities for Medical Practice

Satisfactions for any person are often associated with health and with freedom from disease. It is important to understand how basic scientific knowledge aids in freeing ourselves from disease, and how, if our judgment is wise, it may help us to better our health. Medical practice has recently undergone sharp challenges related to the continuing advance of knowledge of ourselves as revealed by search and research. It may be interesting to examine the advances at four stages in the developmental history of medical practice. These cumulative stages overlap, but the total picture is one of ever-increasing effectiveness.

Under primitive conditions and in emerging cultures, the causes of disease are mysterious and to be feared. Superstitious appeals to beneficent deities or appeasement of malevolent powers are the magical setting for witchcraft medicine. Vestiges of this stage of medical effort remain, largely because the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy in reasoning operates when sick people get well regardless of therapy. Even the ancient Greek physicians recognized these operants in magic or quackery.

The second stage in medical development was empirical. It remains, although the surviving Egyptian medical papyri indicate it was already well advanced as early as 2000 BC. Keen observation, careful recording, rational application of experience, and tender care combined to make medicine and nursing increasingly successful in the management of disease. Sometimes erroneous theory led to excesses, as with the bleedings, purgings, and vomitings so widely used in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The “homeopathic” system was a reaction against these excesses.

Empirical management of sick patients was increasingly successful as symptoms were correlated with structural abnormalities in organs and tissues. Improved diagnostic and therapeutic methods led to better control of the processes of disease, and medical practice continually improved. In the United States, the AMA greatly aided in setting high standards of medical education and medical practice.

The third, or scientific, stage of medical advance began during the Renaissance and accelerated greatly during the past century. The rise of such disciplines as anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, microbiology, pathology, and pharmacology has caused a huge, profitable explosion of precise information on the causes and control of disease. Indeed, by the beginning of the 20th century, there was sufficient information on disease etiology, both infectious and metabolic, to consider seriously the proposition of preventing disease. Preventive medicine, so vigorously championed by William Henry Welch, became part of the medical curriculum. In practice, however, the attempt was unsuccessful because individual physicians could not understand how they could earn a living if disease were prevented. The people took up the effort, and public health flourished despite initial opposition from physicians. Indeed, the success of the public health movement has brought on the population pressures causing worldwide concern.

Actually, the success of the public health endeavor has ushered in the fourth phase of medical effort: the promotion of optimum mental and physical health for people everywhere. This is a tremendous undertaking, but one with great potential rewards. Its basic implication is that the betterment of health has replaced the management of disease as the primary concern of the health professions.

Here is a real challenge to the health professions. Can individual members of the health professions devise methods of teamwork directed to promoting good mental and physical health in individual patients? This suggests group practice, regular advisory sessions with the family, and graduated fees based on the family’s situation, economically independent of professional and hospital services for the sick or injured. Such a system could greatly increase clinical services for examination and consultation while reducing hospitalization for managing disease except in terminal cases.

This phasic development in medical practice has been dependent on the steady increase in verifiable knowledge about people in health and disease. Continuing advances in biomedical science make it possible (1) to treat disease and injury more successfully, (2) to prevent many infectious and metabolic diseases, and (3) to promote healthier living for people both mentally and physically.

These aspects of medical advance will undoubtedly accelerate as members of the health professions encourage further search and research. This is the significance of the AMA’s decision to lead the continuing exploration of the frontiers of molecular biology. From such fundamental studies of immunity, ecology, virology, and the application of physical principles to biological phenomena will come a deeper understanding of the life processes that will enrich human knowledge and, ultimately, enhance the satisfaction and success of those who practice the health professions.

Prospect

The AMA-ERF Institute for Biomedical Research promises to justify the people’s faith in the medical profession and its acceptance of its social responsibility to seek verifiable information about health and disease and wisely apply it to promote optimum health for people everywhere. It offers the opportunity to extend to us all the satisfactions obtained in scientific endeavor aroused by curiosity over how we are made and how we tick, in search and research for truth, not dogma; for understanding, not biased belief; for wisdom, not smug faith; for sanity, not slogans.

Let us not delude ourselves by dreaming that great achievements are imminent. Let us eschew “breakthroughs” lest we incur frustrating breakdowns. Let us strive for equanimity in our quest for the “truth,” remembering that whatever we call “truth” is tentative and subject to revision as our verifiable knowledge increases, and that “even unwelcome truth is better than cherished error.” Let us patiently support the long-term scientific endeavor. It would be brash indeed to think that the secrets evolved over billions of years will yield overnight, even with the most generous financial backing.

From its initial concern with the molecular aspects of the life processes in health and disease, the AMA-ERF Institute for Biomedical Research may grow to encompass cells, organs, tissues, individuals, societies, and ecologies. With this perspective, it might one day study the factors determining judgment and permit us to apply our growing knowledge about ourselves and our environment to the benefit of all and to the preservation of the world from which we evolved. Thus may we approach the ancient Greek ideal of unity in our logics, our ethics, and our esthetics.