October 13, 1975

The Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was an amazingly split-up personality. He was a pious conservative, a dull pedantic teacher of mathematics, a pixieish poet, a weaver of delightful allegories, a nonsensical lyricist, an avuncular admirer of little girls, a pioneer photographer of great skill, and a hospitable bachelor Oxford Don.

The eldest of eleven children of Archdeacon Charles Dodgson and the latter’s cousin, Frances Jane Lutwidge, our split genius was born January 27, 1832, at Daresbury Parish, north of Warrington, in the oak country of old England. His mother was a gentle, sweet woman, who reared her brood well. His father, from a long line of clerics, was a distinguished scholar, having been a double first at Christ Church, Oxford. He imbued his son with a deep and abiding love for mathematics.

Young Charles was a busy boy. He counted snails and toads as his friends. After the family moved to Croft, a pleasant Yorkshire parish, he roamed the grounds, and in the evenings he entertained them all with puppet shows and by writing stories for them. He was sent to Richmond and Rugby but liked neither. His teachers, however, thought highly of him. The Reverend A. C. Tait, headmaster at Rugby, and later Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote Archdeacon Dodgson that young Charles’s examination for the Divinity Prize “was one of the most creditable exhibitions he had ever seen.” Young Charles was clearly well-placed in The Establishment.

While at Rugby, Charles wrote poems and essays for the school literary magazine. He edited it for a while, adding verses, essays, and even caricatures. His sketches were amusing and continued to be so throughout his life.

In 1850, at eighteen, young Dodgson matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford. This was made easier by the prestige of his father. He continued to live there for the rest of his life. The death of his mother in the following year was a blow to him, but it spurred him to work harder. He won a scholarship and first honors in mathematics, much to his father’s delight. He received a studentship and became Bachelor of Arts in 1854. He was then made a “Master of the House” and a sub-librarian.

Meanwhile, Charles Dodgson enjoyed the drama. This continued to intrigue him, especially in his later years when he became a good friend of Dame Ellen Alice Terry (1848–1928), the great Shakespearean actress. In his spare time, young Dodgson wrote light verses and essays for The Train, a periodical developed by the London Times. He also edited College Rhymes at Oxford. Since it was a decidedly “light” publication, he may have felt it beneath the dignity of a lecturer in mathematics. He recognized the need for a pseudonym. The one selected from several proposed was Lewis Carroll: the “Lewis” being a derivative of “Lutwidge,” and the “Carroll” coming from “Charles” or “Carolus.”

His schizophrenia was now official. He was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson in his academic position and publications but Lewis Carroll when fancy-free.

He was ordained a deacon in the established Church of England but never went on to be ordained a priest. Rarely did he attempt to preach. His hesitant speech, with stammering, prevented any distinction as a cleric. Yet, he was proud of being the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, however irreverent he may have seemed at times. At all times, he showed reverence for whatever he considered sacred, even to the “beautiful bodies” of the naked little girls he liked to photograph.

The Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, Lecturer in Mathematics at Oxford, found teaching a bore—something to be dispensed with as quickly as possible. Yet, he was punctilious in his academic duties.

Though a very dull teacher, his hesitancy in speech perhaps made him unsure in affairs. He stuttered and was left-handed, and his speech was slow and hesitant, which frustrated his students. He was not popular with them.

On the other hand, he delighted in entertaining children, especially little girls. He always had his pockets full of toys and gadgets to attract their interest. With them, he seemed at ease and did not stammer. His rooms were filled with games and gadgets to entertain young visitors. He didn’t care for boys and apparently disdained young men as students.

Though he had no enthusiasm for teaching mathematics, Dodgson seemed fascinated with the subject, as his publications show. His subject was geometry. In accordance with academic tradition, he published prolifically. Under his real name, he contributed an astonishing number of conventional works in mathematics, around 42 in all, according to the useful bibliography compiled by Florence Baker Lemon in her delightful Through the Looking-Glass (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1945, 307 pp.).

While the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson made no startling mathematical discoveries, his texts became well known. Before he was thirty, he had published three creditable geometrical works, all issued by Parker of London: Notes on the First Two Books of Euclid (1860), Syllabus of Plane Algebraical Geometry (1860), and The Formulae of Plane Trigonometry (1861).

Much later in his life, in 1896, two years before his death, he published a book on Symbolic Logic (Macmillan, London). This anticipated, by a couple of decades, the exhaustive efforts of Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) and Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) in their very obtuse and extensive Principia Mathematica, published in three volumes in London from 1910 to 1913.

As reported in a charming review by Polly Foreword in 1973, Dodgson’s reputation as a mathematician largely rests on his Euclid and His Modern Rivals (Macmillan, London, 1885). This may have stimulated Martin Gardner, the famed feature writer of mathematical puzzles for Scientific American, to compile his splendid annotated editions of Dodgson’s most famed writings under his pseudonym Lewis Carroll: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Macmillan, London, 1865), Through the Looking-Glass (Macmillan, London, 1871), and The Hunting of the Snark (Macmillan, London, 1876). The introductions and annotations to these books, as edited by Martin Gardner, are entertaining in themselves. They add a wealth of information and speculation to the career of Lewis Carroll, spicing it deliciously.

As might be expected, Lewis Carroll has been the subject of much posthumous psychoanalysis. This ranges from reverse Oedipus complex to impotence frustration. Strangely, no one seems to have commented upon his rather obvious schizophrenia. Yet, it seems to have been a conscious aberration, quite like his conscious Victorian hypocrisy, and his mischievous delight in subtle satire. Some of his almost nauseous “pious piffle” was appended to the 1886 printing of his 1864 Christmas manuscript gift to Alice, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. It is a note entitled Who Will Riddle Me the How and the Why. This is followed by another piece of piety, An Easter Greeting to Every Child Who Loves Alice.

Macmillan, in the ads at the end of the 1886 publication, noted: “Mr. Lewis Carroll, having been requested to allow ‘An Easter Greeting’ (a leaflet, addressed to children, first published in 1876, and frequently given with his books) to be sold separately, has arranged with Messrs. Harrison of 59 Pall Mall, who will supply a single copy for 1d, or 12 for 9d, or 100 for 5s.” It has not been revealed how many were sold, if any.

It is generally agreed that the two Alice whimsies are slyly disguised commentaries on various logics and logical fallacies. In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the gentle but sometimes sarcastic satire is oriented around a pack of cards, with action centering around the King, Queen, and Jack. In Through the Looking-Glass, it moves along a chessboard. In both cases, there is frequently irreverent satire directed at some aspect of the Establishment, usually royalty, as with the King and Queen of Hearts in the last chapters (“The Trial”) of Wonderland, and the unpleasant Red Queen and the unctuous White Queen in Looking-Glass.

Thus the question arises: was Dodgson really trying to put across an allegory on logic? Was he subtly satirizing the Establishment, or was he, as Lewis Carroll, simply spinning a whimsical tale for the amusement of the three young daughters of his superior, Dean Henry George Liddell (1811–1898), the distinguished Greek lexicographer?

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was apparently spun off extemporaneously. The early manuscript version of 1864 was amplified considerably for the 1865 publication. It supposedly was given in sections as Dodgson and his friend, the Reverend Robinson Duckworth (the “Dodo” and the “Duck”), rowed up the Isis above Oxford to Godstow on that supposedly sunny afternoon of July 4, 1862, with the three Liddell sisters: Lorina Charlotte (Prima), aged thirteen; Alice Pleasance (Secunda), aged ten; and Edith (Tertia), aged eight. The trip was about three miles. In his diary, Dodgson noted:

“We had tea on the bank, and did not reach Christ Church again until a quarter past eight, when we took them to my rooms to see my collection of micro-photographs, and restored them to the Deanery just before nine.”

Later, he added on the side, “On which occasion I told them the fairy tale of Alice’s adventures underground.”

The first transcript by Dodgson was actually called Alice’s Adventures Underground. He painstakingly hand-lettered the 90 pages with neat composition, adding many amusing sketches and full-page illustrations. It had a half-title, “A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer’s Day.” It was given to Alice Liddell on November 26, 1864. The book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was considerably expanded from this manuscript. With the extremely skilled and appropriate illustrations by John Tenniel (1820–1914), this book was published on July 4, 1865, by Macmillan in London. By 1886, it had sold 78,000 copies.

The manuscript “Christmas Gift” was sought by Dodgson in 1886 for permission from Alice, then Mrs. Hargreaves, to issue in facsimile. In his letter, quoted by his nephew Stuart Dodgson Collingwood in The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll (London, 1898), Dodgson says, “My mental picture is as vivid as ever of one who was, through so many years, my ideal child-friend.” But he does go on to confess that he has had many other nice little girl friends. Macmillan, after much trouble with the plates, issued the facsimile in 1886.

The original manuscript was acquired by the great Philadelphia bookseller, A. S. W. Rosenbach, after Alice’s death. It cost him $50,000. Luther H. Evans, the keen Librarian of the Library of Congress, persuaded Rosenbach to sell it for the same sum (raised by friends), and in 1948, it was presented to the British Museum. In accepting it, the Archbishop of Canterbury remarked that its return to England was “an unsullied and innocent act in a distressed and sinful world.”

These facts, with many others, are given by Warren Weaver, our long-ago University of Wisconsin friend, in his Alice in Many Tongues (University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1964). Warren Weaver was a distinguished mathematician, an able officer of the Rockefeller Foundation, and Director of the Sloan Foundation, guiding their scientific projects with great skill. As President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he was a powerful influence in promoting high standards for American science.

I recall a dinner club evening in 1924, when Warren Weaver reviewed Whitehead and Russell’s great Principia Mathematica. This had aroused his enthusiasm for symbolic logic, in which Dodgson was somewhat of a pioneer. Weaver amassed a superb collection of Dodgson’s (and Lewis Carroll’s) works, on which he has written well. His appreciation of Lewis Carroll (or Dodgson) as a mathematician is definitive (American Mathematical Monthly, 45:234–236, 1938; Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 96:377–381, 1954, and Scientific American, April 1956).

An interesting use of Lewis Carroll’s whimsical logic, as expressed in the Alice books, was made by Dwight Ingle, a brilliant professor of physiology at the University of Chicago and founder and editor of Perspectives in Biology & Medicine. Ingle took quotations from the Alice books as illustrations of frequent logical fallacies found in biomedical writing. He lists 96 such fallacies, falling into seven categories ranging from the assumption of causal relations in sequential events to generalizations, indifference, verbal fallacies, non sequiturs, and statistical fallacies.

A painful example is Tweedledee’s definition of logic:

“If it was so, it might be; and if it were so, it would be; but as it isn’t, it ain’t. That’s logic.”

This illustrates Dodgson’s keen appreciation of what we call semantics. It suggests that he used words carefully, despite writing, as Lewis Carroll:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “It means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

But, as Alice said, “The question is, whether you can make words mean so many different things.” The fallacy of amphiboly—using words in more than one sense—is related to punning:

“And how many hours a day did you do lessons?” said Alice.

“Ten hours the first day,” said the Mock Turtle, “nine the next, and so on.”

“That’s the reason they’re called lessons,” the Gryphon remarked, “because they lessen from day to day.”

A frequent error in biomedical writing is wordiness instead of directness, as in the case of someone who would answer the question, “What time is it?” by explaining how to make a watch. Lewis Carroll illustrated this well:

“I quite agree with you,” said the Duchess, “and the moral of that is—‘Be what you seem to be’—or, if you’d like it put more simply—‘Never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others that what you were or might have been was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise.’”

The classic logical fallacies are well illustrated in the Alice books and in The Hunting of the Snark. They range from post hoc ergo propter hoc through pars pro toto, plurium interrogationum, dicto simpliciter, non sequitur, petitio principii, and various arguments to the excluded middle and assumptions. Carroll’s classical education would have familiarized him with the meticulous details of medieval logic.

What about the logic, if any, of Carroll’s “nonsense” in poetry or prose, verse or “worse”? Some of it is plainly humorous wordplay. Take, for instance, the conversation between Alice, the Mock Turtle, and the Gryphon, as recorded in Wonderland. The Mock Turtle mentions his school subjects:

“Reeling and Writhing, of course, to begin with, and then the different branches of Arithmetic—Ambition, Distraction, Uglification, and Derision.”

“What else?”

“Well, there was Mystery, ancient and modern, and Seaography, then Drawling—the Drawling master was an old conger eel—taught us Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils—Old Crab, the Classical master, taught Laughing and Grief.”

The Alice books contain many “nonsense” verses. One of the most famous is a clever parody of The Old Man’s Comforts by Robert Southey (1774–1843):

“You are old, Father William,” the young man said,

“And your hair has become very white;

And yet you incessantly stand on your head—

Do you think, at your age, it is right?”

“In my youth,” Father William replied to his son,

“I feared it might injure my brain;

But now that I’m perfectly sure I have none,

Why, I do it again and again.”

Carroll was a master wordsmith. He took a “nominalistic” view of semantics; that is, as Martin Gardner noted in Dodgson’s Symbolic Logic, “I maintain that any writer of a book is fully authorized in attaching any meaning he likes to any word or phrase he intends to use.” There is the qualification, however, that he explain the meaning and remain consistent in its use. As Humpty Dumpty said, “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

In acknowledging Humpty Dumpty’s cleverness at explaining words, Alice asks him to tell the meaning of the poem called Jabberwocky. Humpty replies, “I can explain all the poems that ever were invented—and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet.” So Alice offers the first verse:

“’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.”

Humpty Dumpty explains that “brillig” means four in the afternoon, the time for broiling things for dinner. “Slithy” means “lithe” and “slimy.” “It’s like a portmanteau—there are two meanings packed up into one word.” Portmanteau words are now common, like “smog.” James Joyce was a master at such contractions.

Jabberwocky is one of the most famous “nonsense” poems. Clearly, Lewis Carroll enjoyed composing it. Many of the unusual words in it can be traced, as Martin Gardner has done, to old English usage.

When did Dodgson find the time to do all the things he did? Consider the acrostics in the verses dedicating The Hunting of the Snark to his little girl friend, Gertrude Chataway. But, as Martin Gardner notes, Dodgson could extemporize acrostic verses in presentation copies.

The longest and most famed of Lewis Carroll’s “nonsense” rhymes is The Hunting of the Snark, issued by Macmillan in London in March 1876, with realistic illustrations by Henry Holiday, who was famed as a designer of stained-glass windows. It may readily be assumed to be a subconscious “existentialistic” document. In fact, Dodgson (or Lewis Carroll) called it “An Agony, in Eight Fits.” This recalls the powerful emotional drama of Søren Aaby Kierkegaard (1813–1855), and the “agony” expressed in his Either/Or (1843). Kierkegaard was the forerunner of “existentialism,” which became so popular under the influence of Jean-Paul Sartre (1910–1980), Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), and Martin Buber (1878–1965). These all wrestled with that basic question which so profoundly troubled Hamlet: “To be or not to be.”

This question, which I have expressed as “What are we living for?”, raises many others: what motivates us? What guides our conduct? What governs our interpersonal relations, and what determines our moods and behavior? The answers to these questions, which have been rather well formulated over the centuries, comprise the various “ethics,” as I have tried to show. While the existential answers tend to be highly subjective, Lewis Carroll seems to have posed both the questions and answers in a peculiarly surrealist, objective manner. Did he know of Kierkegaard? The articulate existentialists have been theologians, and not particularly reverent ones at that. The Reverend Charles Dodgson was at his irreverent best as Lewis Carroll. As the Reverend Mr. Charles Dodgson, he repeatedly denied responsibility for the writings of Lewis Carroll.

Writing in 1887, Lewis Carroll says that on July 18, 1874, he “was walking on a hillside, alone, one bright summer day, when suddenly there came into my head one line of verse—one solitary line—‘For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.’ I knew not what it meant then; I know not what it means now, but I wrote it down.”

He goes on to relate how he added to it over the next couple of years until it was complete. At first, he hoped to have it out for Christmas 1875. Delays with the illustrations held it up until Easter 1876. Perhaps to offset the irreverent style of the ballad, he inserted an “Easter Greeting,” a rather sentimental bit of piffle.

The surrealistic tone of Carroll’s masterpieces—the two Alice books and The Snark—has something of the same emotional thrust as abstract painting or Rorschach ink-blots. They deal with what is in-between being and not being, with what neither is nor isn’t, like the grin of the Cheshire Cat. They are neither reasonable nor unreasonable; neither sensible nor nonsensical; and one lost in them may be neither awake nor asleep. This reminds one of the very ancient riddles associated with the ritual deaths of Hero-Kings in the second millennium B.C.

There was Indra in India, not to be slain by day nor night; neither with staff nor bow; neither with the flat of hand nor fist; neither by anything wet nor dry. There was Agamemnon at Mycenae, to be killed neither wet nor dry; neither clothed nor unclothed; neither in his home nor away. And there was Lleu Llaw Gyffes in Wales, to die neither at home nor away; neither on horseback nor on foot; neither in water nor on land, and neither clothed nor unclothed.

Did Lewis Carroll really not know what he was writing about? Martin Gardner refers to five occasions when Carroll said that he did not know what it was all about. He seems to have favored the idea that it is an allegory on the search for happiness in which we all engage; when we think we’ve found it, there’s nothing there. Others have made of it an allegory on business success. Others have spoofed it as an allegory of the search for the Absolute.

There are peculiarities about it. The ten characters on the search for the Snark have names beginning with B: Bellman, Butcher, Banker, Beaver, Broker, Barrister, Bonnet-maker, Billiard-marker, Boots, and Baker. The Snark (a portmanteau word, which Carroll says is made up of “snail,” or “snake,” and “shark”) turns out to be a Boojum, which was the end of the Baker, as his uncle foretold.

“In the midst of the word he was trying to say

In the midst of his laughter and glee,

He had softly and suddenly vanished away—

For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.”

Henry Holiday’s fearsome sketch of the Boojum was rejected by Carroll for the 1876 book, but it was published by Martin Gardner in his fine annotated edition of 1962. Holiday did not attempt to portray the “Bandersnatch,” who so scared the Banker in his dream that his waistcoat turned white.

As Martin Gardner emphasizes, Lewis Carroll was obsessed with the letter B. One of his early verses was signed B. B. The scary character of the Boojum is clear from the way children often say “Boo!” when they wish to startle someone who does not see them. The Bandersnatch, appearing only in a dream, is certainly a scary creature as well. Both exist in dreams or imagination and both are truly not present in objective reality. Both are in between.

Our irreverent Reverend seems to have been in between too. When being Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, he was not being Lewis Carroll, and when he was being Lewis Carroll, he was not being Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. His “to be or not to be” may have been quite clear, at least to him.

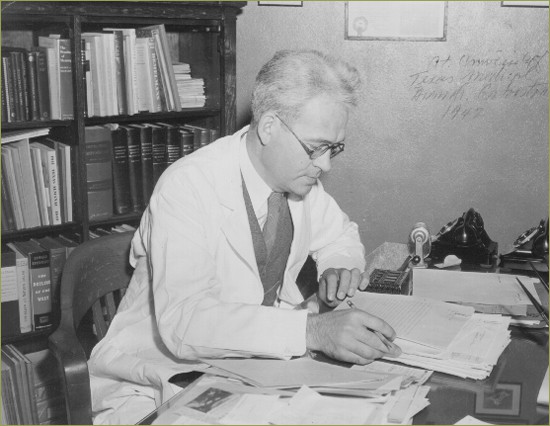

Clear indeed was the Rev. Mr. Charles Dodgson in his photographic interests. He was a skillful photographic artist in an exciting new art medium. Technical improvements had made photography popular by the middle of the 19th century. The comparative ease of the “wet collodion” plate method enticed all sorts of people into home photography. Even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert had a photographic darkroom constructed at Windsor Castle. And Charles Dodgson was a leader in the new art, at least around Oxford. Not only did he have sittings in his room, but he also took the cumbersome equipment on journeys into the countryside and seaside to photograph his friends in natural surroundings.

Instead of the usual, rather ridiculous backdrops of painted mountains and waterfalls, Dodgson posed his sitters naturally and achieved amazing psychological studies thereby. Of course, he took pictures of Alice Liddell, and charming ones they are. He made pictures of his sisters and brother at Croft. He persuaded many famous people to sit for him, including Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), John Ruskin (1819–1900), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) and his family, Michael Faraday (1791–1867) the great chemist, and a host of prominent clergy. Though he lion-hunted almost ferociously, he hated to be lionized himself and resisted anyone taking a picture of him. There are a couple of portraits of him, however, and they reveal a sensitive, shy, pensive, rather delicate man.

Dodgson kept careful files of his negatives and photographs. He compiled several of the photo albums that were popular in Victorian homes, often a common ornament on sitting-room tables. At the auction of his effects in 1898, they went for a few shillings each. Now they form important parts of great libraries, with one group being part of the Morris L. Parrish Collection at Princeton, and another part of the Helmut Gernsheim Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

Daniel White, in describing the Parrish photographs, pays tribute to Dodgson’s artistic skill (Princeton Alumni Weekly, May 28, 1974):

“Many of Dodgson’s photographs portray a mood of lassitude, dreaminess, and preoccupation with a private world. Nor are we supposed to find out more than the camera shows. The eyes, windows into her soul, avoid the camera.”

These comments apply particularly to the many pictures Dodgson took of young girls, including the famous one of Alice in profile. In commenting on Dodgson’s photo portraits of Tennyson, White emphasizes Dodgson’s skill in throwing full light on Tennyson’s forehead to suggest intellectual power. In his group photos, as with his sisters at Croft, Dodgson posed them quite naturally, avoiding the conventional stereotypes of the period.

A full account of Lewis Carroll as a photographer has been made by Helmut Gernsheim (Dover, New York City, 1969, 127 pp., with 64 plates). In this, Gernsheim, a distinguished historian of photography, praises Dodgson highly for his artistic and technical skill. He also adds much to our knowledge of Dodgson’s private life. This resulted from Gernsheim’s personal contact with Dodgson’s relatives and friends. One of these was Wing Commander Caryl Hargreaves, son of Mrs. Reginald Hargreaves (formerly Alice Liddell). He wrote to Gernsheim confirming the notion that Dodgson was in love with Alice Liddell, saying that Dodgson had asked her parents’ permission to marry her, but they refused. It is interesting that Alice named her son “Caryl.” For her long interest in the best of English literature, Oxford University awarded her an honorary LL.D. in 1932, when she was eighty years old.

One of the results of Gernsheim’s enthusiasm was the opening of Dodgson’s diaries, which he had kept from 1855 to 1895. There is a gap in the diaries—entries from 1861 to 1867 are missing. They are supposed to have been removed by Dodgson’s over-cautious nephew and biographer, Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, to avoid gossip over Alice.

There was some sort of scandal, however, around 1880. At that time, Dodgson suddenly gave up photography entirely. He resigned his lectureship in 1881 and declined invitations to social events. It may have had something to do with his passion for photographing little girls undressed. All the evidence, however, from subjects and their mothers, indicates that Dodgson preserved every proper formality. But something happened. Dodgson became retiring and aloof. He feared that he would not be able to complete his writing. He did complete a two-volume sugary fairy tale, Sylvie and Bruno, in 1889, but its moralizing tone doomed it to failure.

He may have been impelled to try to balance his early fantastic Alice allegories and The Snark with something morally uplifting. It was a failure. He did publish his Symbolic Logic in 1896 under his real name. In withdrawing from the world, Dodgson retreated with nostalgia to a happier, earlier time. Always, this nostalgia seemed to haunt him. He closes Through the Looking-Glass of 1871, when Alice was 19, with an echo of the day in 1862 when he first told the story of Wonderland:

A boat beneath a sunny sky

Lingering onward dreamily

In an evening of July—

Children three that nestle near,

Eager eye and willing ear,

Pleased a simple tale to hear—

Long has paled that sunny sky:

Echoes fade and memories die:

Autumn frosts have slain July.

Still she haunts me, phantomwise,

Alice moving under skies

Never seen by waking eyes,

Children yet, the tale to hear,

Eager eye and willing ear,

Lovingly will nestle near.

In a Wonderland they lie,

Dreaming as the days go by,

Dreaming as the summers die:

Ever drifting down the stream—

Lingering in the golden gleam—

Life, what is it but a dream?

This poem echoes the themes of winter and death that run through the opening poem of Looking-Glass. The poem is an acrostic, with the initial letters of the lines spelling Alice’s full name.

In Looking-Glass, the most appealing character is the White Knight, often thought to be a caricature of Carroll himself. In the introduction to the song “A-Sitting on a Gate,” Carroll pioneers in what is now known as “metalanguage,” which semantically involves “metalogic.” It attracted the attention of Bertrand Russell and also of the great physicist Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882–1944).

The scene opens with an example of the logical fallacy of the excluded middle:

“Everybody that hears me sing it—either it brings the tears into their eyes, or else—”

“Or else what?” said Alice, for the Knight had made a sudden pause.

“Or else it doesn’t, you know.”

The account of the names of the song seems to be confusing. As Martin Gardner says, however, it is not so for a student of logic: The song is “A-Sitting on a Gate”; it is called “Ways and Means”; the name of the song is “The Aged Aged Man”; and the name is called “Haddocks’ Eyes.” The distinction is between things, the names of things, and what these names are called. What a name is called belongs to “metalanguage” and involves “metalogic.” Such a convention of a hierarchy of metalanguage enables modern logicians to sidestep such ancient Greek paradoxes as those proposed by Zeno in the 5th century B.C.

There is so much more of Dodgson-Carroll, or “Dodoll,” (to bring them together), that I despair of doing justice to it. How about his trip to Russia in 1867? This has been edited from his diaries by John Francis McDermott in 1935. Or why did he not like American children? Or how about the little girls who came to his rooms to be photographed and enjoyed romping about naked while their mothers watched? Or how about the technical skill involved in the photography? Daniel White says of it:

“Speedy as the collodion process was, it was no less temperamental and cumbersome than the daguerreotype. The glass plates had to be polished to ensure chemically clean surfaces. The glass (Dodgson used 8″ x 10″ plates) had to be balanced in one hand while the silver nitrate solution was poured on evenly. The slightest touch against any foreign substance ruined the surface of the plate. Development of the negative occurred in the same fashion. The photographer-chemist-juggler, as he was, must then varnish the plate to prevent further exposure, then sensitize, tone, and fix the prints.”

Dodgson must have been a considerable chemist to prepare the several solutions and to have measured the ingredients correctly.

While Dodgson usually dropped his little girl friends when they entered their teens, there were exceptions: Alice Liddell, who later married, and Gertrude Chataway, who maybe didn’t. Dodgson met Gertrude in 1875 on the beach at Sandown, a bathing resort on the Isle of Wight, where she was with her parents and sisters. She was eight. Dodgson made a charming pencil sketch of her in “boyish garb.” When she was 25, Dodgson wrote her an affectionate letter, recalling “like a dream of fifty years ago, the little barefoot girl in a sailor’s jersey, who used to run up into my lodgings by the sea.” In his diary for September 19, 1893, Dodgson notes that Gertrude, then 27, arrived for a visit at his lodging in Eastbourne, his favorite seaside resort. The next entry in the diary is four days later: “Gertrude left. It has been a really delightful visit.” Nine days before the visit, Dodgson had preached a sermon at Eastbourne, a most unusual thing for him to do, on the text, “Lead us not into temptation.” He had received a letter from a sister raising the question of whether it was proper for him to have young ladies, unescorted, visit him at the seaside. He replied that it was a matter of his conscience and the approval of the parents.

Gertrude herself, recalling the occasion, as reported by Stuart Dodgson Collingwood in 1899 after Dodgson’s death, said:

“I don’t think that he ever really understood that we, whom he had known as children, could not always remain such. I stayed with him only a few years ago at Eastbourne, and felt for the time that I was once more a child. He never appeared to realize that I had grown up, except when I reminded him of the fact, and then he only said, ‘Never mind: you will always be a child to me, even when your hair is grey.’”

Dodgson certainly had the ability to dream, even as he was getting old. As a dreamer, he was the charming tale-teller, Lewis Carroll; as a person, he was Charles Dodgson, dull mathematician. Better this than Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

When you try to figure out how it could be,

It becomes very complicated, you see,

To tell when Charles Dodgson or Lewis Carroll is he;

But that’s the way it has to be.

For Lewis Carroll was Charles Dodgson, you see.

But that is only one way he could be,

For Charles Dodgson was Lewis Carroll, you see.

Thus it is as clear as clear can be,

And we’re finding our Snark, that you’ll agree,

So we can sigh or shout with glee,

And softly and suddenly cease to be,

For our Snark was a Dodoll—a Being, you see.

I well realize my inadequacies in trying to say something sensible about Charles Dodgson–Lewis Carroll, or “Dodoll” as he might have called himself had he possessed a bit of self-reliant humor. Who can do justice to such a multifaceted character? Stodgy mathematician, dull and boring teacher; asymmetrical stammerer when formal; delightfully fun-loving when relaxed and informal in the company of the little girls he loved; weaver of dreamlike tales, which, though amusing, still conceal deep and obtuse speculation on tricky logical problems; extraordinary pioneering photographer; and ordained Deacon, usually too hesitant to preach. What can I say of him, except that he was indeed an irreverent Reverend.

Reminders of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865), Through the Looking-Glass (1871), and The Hunting of the Snark (1876):

Alice in Wonderland has 12 chapters:

- Down the Rabbit-Hole

- The Pool of Tears

- A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale

- The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill

- Advice from a Caterpillar

- Pig and Pepper

- A Mad Tea-Party

- The Queen’s Croquet-Ground

- A Mock Turtle’s Story

- The Lobster Quadrille

- Who Stole the Tarts?

- Alice’s Evidence

Through the Looking-Glass also has 12 chapters:

- Looking-Glass House

- The Garden of Live Flowers

- Looking-Glass Insects

- Tweedledum and Tweedledee

- Wool and Water

- Humpty Dumpty

- The Lion and the Unicorn

- “It’s My Own Invention”

- Queen Alice

- Shaking

- Waking

- Which Dreamed It?

The Hunting of the Snark is “An Agony, in Eight Fits”:

- Fit the First: The Landing

- Fit the Second: The Bellman’s Speech

- Fit the Third: The Baker’s Tale

- Fit the Fourth: The Hunting

- Fit the Fifth: The Beaver’s Lesson

- Fit the Sixth: The Barrister’s Dream

- Fit the Seventh: The Banker’s Fate

- Fit the Eighth: The Vanishing

It is interesting to note that both Looking-Glass and The Snark contain the literary device of a “dream within a dream.”