March 14, 2023

They say that confession is good for the soul.

Being scientifically-oriented, I am eager to test the limits of that advice. So I am going to make a stab at confession tonight, since I have the good will of everyone gathered together here — well, at least a little good will or you would have skipped our dinner tonight and found something better to do, like watching TikToks of cute kittens playing with even cuter toddlers. But you are here instead, so please indulge me in attempting something that is supposed to be good for my soul.

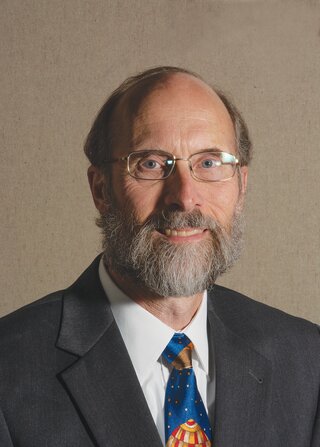

Now that I have reached the Biblical height of three score and ten years, I feel it is high time for me to be more honest — especially since turning 70 used to mark the final curtain for those few still left standing, according to Psalm 90. Nowadays it is more often the start of a person’s second or third act. Since I am a realistic optimist, I am hoping to squeeze in a few more lines before that curtain falls. But I do figure, no matter what else happens, that the rest is gravy — which is an odd thing for a vegetarian to say. But I was raised in Wisconsin on meat and potatoes. And lots of gravy.

So I thought I would start off my seventies with a bang — with a little too much honesty. Not that anyone really wants me to be any more honest than I already am. But many of my well-meaning Catholic friends think I don’t have much time left to change my habits, and so have suggested that I start going to confession again — having left off that habit when I was still too young to have committed any truly mortal sins.

So I would like to confess to all of you that I have been keeping under wraps an important secret nearly my whole adult life. Some of my closest friends and family members know this secret, but most of you do not.

Fortunately, our current culture is forgiving — as long as you confess to your weakness, you are not browbeaten about it. Instead, you are encouraged to “own it”. Even so, at my age honesty is probably still not the best policy. But it is obviously much safer now than when I was younger to indulge in a little honesty — being retired and all — so I have decided, after over 50 years of keeping my secret under a bushel basket, to “own it”. Big time.

So whether you like it or not, I am going to share with you my secret: I have a serious drinking problem. This well-kept secret — one keeps a secret because it is socially unacceptable — has been especially well-kept because my secret drinking problem is far more socially unacceptable than the much more popular versions of having a drinking problem.

You see, my drinking problem is not that I drink so that I forget. It is that I don’t drink so that I don’t forget. This has created a surfeit of memories that has left me in a quandary my whole adult life. Let me explain.

I did not drink enough when it was incumbent upon me to drink deeply. I am speaking now about drinking from the River Lethe. Long, long ago I started skipping that post-death ritual, just as a lark to test the rule.

But there have been unintended consequences. For one thing, it has dramatically increased my attention to Alethia — literally “not forgetfulness” — or Truth. Of course, there may be some literate types among you who are now concluding that that could be why I don’t have the average amount of lethargy. But my guess is that that is unrelated.

What I don’t have, because of my many failures to perform the required ritual, is an unburdened memory bank. No. My memory bank is stuffed with old coins, and sea shells, and bits of thread that seemed so valuable to me at the time when I first experienced them that I have foolishly failed to forget them.

I was hoping you would like to hear about a few.

On March 6, 1982, my 29th birthday, while I was meditating in Madison, Wisconsin, I remembered images of myself as Nor Sim Tim walking into a small village. I had been born in about 5,000 B.C. in a village somewhere in the lands where India and China now rub up against each other. In the center of the village, where perhaps 80 people lived, there was a very large dung heap. The village elder was sitting on top of the heap, with two others sitting near him slightly downhill. The three of them were chanting, so I watched, and waited, and when they were done chanting I asked them about their ritual. They said that they believed the dung had purification powers, and that they were praying to their god to ensure that they were virtuous enough to deserve a good harvest.

I restrained my amusement and explained that if they spread the dung over the dirt where they grew their crops they might get a better harvest, but that sitting there praying was not likely to have any beneficial effect. The village elder got angry, and his shouts soon attracted all the villagers, who surrounded the dung heap to listen to our conversation. The village elder made a claim about the spiritual powers of the dung, and I dared to counter his assertion by saying that his clearly visible skin disease was most likely caused by the unhealthy effects of sitting on dung. To prove he was correct, he took some dung and started rubbing it over his skin lesions. I could no longer restrain myself. He looked so ridiculous in his self-righteousness that I started to laugh.

His fury was overwhelming, and some villagers quickly grabbed me. Several others picked up two small boulders, each about twice the size of my head, and brought them to the village elder while those who had grabbed me plucked my eyes out. And then the village elder, with assistance, crushed my head between the boulders. This all hurt immensely, but I couldn’t stop laughing. And I couldn’t stop thinking “what the hell am I doing, living my life going from village to village, trying to change the way these people think?”

And then I died laughing.

Would you like to hear another?

On January 6, 1995, I fell asleep in my chair after meditating in Frankfurt, Germany. My lucid dream that followed was clearly a memory — I was remembering a scene from my life in Tibet about 4,000 B.C. My name was Gling Glee Ah. What I remember is that while I was making love to my wife in our small cottage her brothers walked by at that very inopportune time — and our door was open. Embarrassment is apparently a rather effective emotional tool for etching lasting memories.

I know when and where I had these memories because I wrote them down in the literary notebooks I have been keeping since 1975. I have eighteen of those notebooks, filled with hundreds of ancient memories, and also filled with my ideas for my novels and my philosophical essays.

Most of my memories make a lot of sense. I remember them because something important happened to me, and I intensely wanted to understand what happened more thoroughly, but at the time of the experience I didn’t have a good theoretical basis for doing that. So I held onto the memory until I could understand it better. That habit has been highly influential in helping me build an ever more effective philosophy of life to live by.

Occasionally a detailed memory does not follow that pattern, but rather seems to have been remembered for no other reason than that I enjoyed the experience — or in one case, the card game.

In the summer of 1980 I had particularly striking memories of a life in northern India about 3,000 B.C. I could see myself sitting on a dais on a large wooden stage set up near the crest of a small hill. There was a crowd of thousands, maybe even 10,000, seated or standing on the hillside, there to watch me die.

I was old, quite old, certainly over 70 years old. Seated on the dais next to me was my wife. We were both dressed in white. Slightly forward on the stage were four more daises, two to each side of me. On each one was one of our adult sons, ranging in age from about 50 to about 35. Our oldest son was seated furthest to my left. On my immediate left was our second son. On my immediate right was our third son. And seated furthest to my right was our youngest son. They were each deep in meditation.

I looked out at the thousands of people, all watching silently. I spoke to them. My voice carried over their silence, as I had been giving public lectures for decades.

Our sons and my wife kept their eyes closed as I spoke. They were expectant, although with a tinge of sadness, and my wife was a bit anxious for me. She was thinking this might not work and that people would laugh at me.

I told the thousands of mostly rural Indians, many of whom I loved dearly after having been deeply involved in their lives for years, that the time had come for my mahasamadhi. I briefly explained that concept, the final merger with the Divine. I explained that all human life moves inexorably towards that goal, that it is the goal of all individual life. And I told them I had finally reached that goal after many, many lives of focused attention on achieving it.

And then I looked at each of my sons. In turn they opened their eyes as my attention went to them. We shared a glance. They all understood. They were each men like me. We had very similar personalities, and they knew I would succeed.

I turned to my wife to say goodbye. She tried to hide her anxieties from me, although she knew she couldn’t. I spent time gazing into her eyes, appreciating her tender affection — the last experience I wanted to have. The experience I wanted to be remembering as my individual mind dissolved forever.

Then I closed my eyes and settled into a deep meditative state. I simply willed my death, my merger with the Divine, my mahasamadhi. There was no other magic to it. It was my freely chosen desire.

Within moments I was outside my body looking down on this whole scene. I knew my wife knew I had passed on, because her heart soared with pleasure, a pleasure heightened considerably by her relief that I had succeeded. Our sons remained deep in their own meditations, but they each knew. And the thousands gasped, amazed and entertained and impressed and very happy they had traveled to see this oddity, this unusual demonstration of the power of yoga. Many of them were also disappointed (and not just a little) that I had succeeded, because they had been anticipating another pleasure, the pleasure of seeing me fail.

And I? I was thoroughly confused, because I was still there. I was still an individual. Something had gone seriously wrong with my mahasamadhi. And that is why I still remember this experience in such detail.

On July 18, 1980, memories from about 4,000 years ago of being a mischievous boy in a caravan town between Damascus and Babylon flooded my thoughts with images and a full life history. I called myself Elohan (though I am not sure if that name is correct) and I was the ringleader of two younger boys, leading them into one mischievous misadventure after another. Nothing serious, but certainly disruptive.

When I was about ten years old, and my mother was pregnant, a trader passing through town had a long discussion with her. I watched them from a distance, and my mother glanced over at me several times. Then the trader handed her a few coins, which she slipped inside the sleeve of her robe, and the trader walked up to me. Just as I realized something was amiss, another man grabbed my arms from behind, as the trader looked me up and down. My mother was already walking away, but she looked back, and the last look she gave me was one of complete exasperation.

The trader was headed to Babylon, and he had bought me from my mother to sell as a slave there. I suffered all night from my mother’s rejection, but once I was walking next to a camel, headed towards Babylon as part of a small caravan of about ten camels and eight men, I got excited thinking about the adventures waiting for me there.

Babylon did not disappoint my imagination. Walking into the city, I remember how striking the buildings were on each side of a fairly wide street, since they had second stories to them. I was taken to one of those buildings and tied to a stake in the wall by the man who bought me from the trader. Before long I was sold in the marketplace, and I got very lucky, because I was bought by a priest-mathematician.

I spent about a decade as the priest’s slave, who figured out quite quickly that I was trainable. He had me help him with his astronomical calculations for his religious rituals, and he also taught me how to read and write. Living in this big city, home to maybe a few thousand people, and adorned with three or four large, beautiful buildings at the city’s center, I rarely missed home. But after a while I started missing my adventures.

When the priest became ill, and old (for then), he talked to me very kindly, and made sure that the other priests knew that he wanted me to be free after he died. So I began to plan a big trip. I even talked two of my friends into coming with me. We intended to raft and walk our way to a rumored sea of salt water by following the Euphrates River downstream.

My owner overheard me talking about my plans, and encouraged me to leave sooner rather than later. He did not trust the other priests to let me go. So he wrote a letter to a priest he knew several days downstream, as a cover story for my departure, and my two friends and I set off on our big adventure.

One memory I have had many, many times is from about 2,600 years ago, as I was sunk up to my chest in muck, a harness under my armpits to pull me out if I gave in. I was suspended in an old well for over a week. I could feel tiny animals burrowing into my skin. My head was about ten feet lower than the upper rim of the well, and there was diffused light during the day. At night it was pitch black. I had not been fed since I was imprisoned in the well, but I had been given water, lowered down to me. I was guarded, but never spoken to. I remember that I did not give in.

On October 26, 1980, I was meditating in Madison, and revisiting various images I had been remembering during the last few years of a man wearing a turban, wielding a scimitar, about to attack me. I had the thought that I would like to discover their context, and my memory swept open, with a very clear experience of the attack, and the related life history.

My childhood memories from that life include being trained to care for horses, and the pleasures of working with horses — bringing the food to the horses in buckets, carrying away their manure in buckets, and petting them on their necks. There were dogs running about the farm where I was trained, too, but I remember feeling they were not at all competitive with horses for grandeur of character.

When I was about 12 years old I was apprenticed to a knight, and I remember thinking he was fine, but not so fine as I had been dreaming of. We got on well, though, and I was chosen to accompany him as his squire on the Crusade to the Holy Land then being organized. We left England when I was about 14 to meet up with Richard the Lionhearted’s forces someplace else, and I remember being excited that I would get to see the King. That made me relatively patient during the exhausting travel.

And then those earlier memories dissolved while I was meditating, and were replaced by seeing myself sitting on a small horse, with a battle about to commence. My horse carried backup weapons for my knight, but I was not myself dressed for battle. I was about 15 years old, and I was wearing simple clothes, with no protection. My orders were to stay near my knight, but out of his way, so that I could resupply him if needed. Richard’s army had arrived in the Holy Land weeks earlier, and his knights had already had a few successes, but this was our first battle where the Saracen leader, Saladin, would be leading our enemies.

My own knight had advanced in the hierarchy due to his bravery in battle, and so he fought about ten knights away from the King, whom I could see sitting on his large horse. Richard was an enormous man, and fought with larger weapons than usual too. He was calm and obviously in command. All the knights were proud of fighting with him.

Not that far from the line of Crusader knights was a line of Saracen knights on horses, with many soldiers on foot behind them. My horse and I were somewhat off to the side, watching alertly as I was supposed to, when the battle cries commenced and both sides started charging at each other. I had never witnessed anything like it, and I stared at the Saracens charging towards us. The bloodlust on their faces, and in their eyes, heightened by intense fear, convinced me that our Christian civilization would triumph.

The next second I attended to my duty and focused on my knight, who was charging towards the Saracens. But I was shocked to see the exact same bloodlust and intense fear in his eyes. I was further stunned when I noticed that the dozen Crusaders whose faces I could see shared the same look. And then I saw Richard’s face similarly distorted.

The shock of that recognition immobilized me, even though I saw that a Saracen knight was charging right at me. The bloodlust in the Saracen’s eyes drew me in, and I was staring at them in disbelief as he swung his scimitar down onto, and through, my left clavicle and split my side open down to my heart.

In my meditation, where I had just relived this death, the physical pain was momentary. But my split-second realizations — that the fine and glorious talk about war, about the Crusade, about knights, and even about the King, were all illusions — those realizations have lingered long, as if they have all been subconsciously vibrant within me from that day in 1191 on.

And now for that card game I mentioned.

On November 21, 1979, I dreamt that my family was playing a card game. Each person was dealt eight cards, and we used two decks. Your turn consisted of picking a card, and then discarding one, so you always kept eight cards. If you got all four 10s, it was called the Black Death. It won. Four aces also won, unless someone had the Black Death. The goal of the game was to get three sets of three cards each (with no last discard) and each set must total 19 points (for example, a 10, a 5 and a 4 would equal one set). The first one with three sets of 19 points each won — unless someone got either the Black Death or four aces first.

When I woke up, remembering all those card game details, I wondered if there ever was such a card game, or if I had concocted all those details in my dream. So I recorded the details just in case some historian finds medieval artifacts that demonstrate a similar card game called The Black Death actually existed around 1500 A.D.

This has been my adult life — filled with memories, observations and conclusions from ancient times. But I am a rational man. What was I to do with all these memories? How was I to make sense of them? I often asked myself in my early 20s if there was any way to be rational about life after death. And before birth.

My answer eventually was the same as for any of our other experiences, including dreaming and our wide range of emotions, all of which (including their very existence) carry a whiff of the ineffable.

That answer was to pursue any patterns I could find, any distinguishing characteristics I could perceive, that would allow me to decipher these ancient memories, to determine what really happened, what was dreamt, what was imagined, and what was deceptive (either intentionally or unintentionally), just as one would sort out memories and experiences from one’s current lifetime.

As part of my attempt to deal with these memories rationally, I am going to ask a favor of each of you — but only if you are interested, of course. I have prepared sample chapters of my 12th book, which I call Ancient Memories, for potential publishers. Deciding whether I should ever publish it has been on my mind for over four decades.

So, if you are willing to read those sample chapters — about 20,000 words total — I would appreciate it if you would then tell me whether you think publishing Ancient Memories is advisable. And why. Or why not. I couldn’t imagine a better set of advisors for this task, as it requires discretion, good judgment and a serious weighing of the advantages, and obvious disadvantages, of me going out on this limb. Of course, after procrastinating for so long, it is no longer such a long limb — I am 70 years old after all.

As to why I am considering doing such a thing at all, I should also confess that I complained bitterly in my last life that no one ever comes back and says what’s really going on. As usual, when it sounds like I am complaining, I am really just egging myself on. And now ― now — well, I certainly can’t say that I know what’s really going on everywhere, but I think I can clearly present the outline of what has been going on in my personal case. And I can also say quite clearly ― probably way too clearly — what can’t possibly be true about what others have claimed to be the Answer to the most important metaphysical questions.

My final confession is that I find it hard to resist testing an old theory of mine – that only laughter can blow a humbug to rags and atoms at a blast. Of course, I am hoping that only a few of you will think that the wisest thing I have done in my life was to keep my mouth shut for so long. But even if that becomes the majority view, it will merely demonstrate why I did it.

I also feel compelled to leave my cave of privacy because I believe I can diminish the unnecessary fears of my friends. We have, after all, been scaring ourselves silly for millennia. And it is my intent to put a massive dent in those fears using the only truly effective weapon against such humbugs — humor.

I know I should have been willing long ago to put up with the consequences of speaking up for that reason alone. But I am a coward, like everyone else, so I’ve waited until I’m old, and have already lived most of my life, before even thinking of stepping out to accept any such consequences.

So, friends, please weigh in on how you think I should answer the following question:

That is the question.

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of unpublished memories,

Or take arms against a sea of publishers,

And, by persuasion, convince them?