Chit-Chat Club

May 13, 1974

First, I should like to thank you all for the privilege and pleasure of coming back to the Club this evening. My first thought when Fred Searls asked me what my title would be was to read a paper on inflation—a subject on which I have some old-fashioned ideas. But it seemed to me that it might be more in the Club’s tradition if I tried to outline the theory out of which inflation came.

I chose the title because Lord Keynes ended his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by asserting that:

“The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Practical men, who believe themselves exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

Keynes wrote this in 1936, and now he is himself defunct and the best proof of his dictum.

The paper I shall read was the final lecture in a series I gave as part of the centennial celebrations of the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. Having discussed what economics was and how economic ideas originated, I traversed very rapidly the elaboration of economic theory, and finally came in my last lecture to Keynes.

My broad argument was that developing technology constantly undermines the assumptions on which economic theory is built. I suspect it does so also in law and other fields of social study. So I argued to the staff and students of the department in which I was raised and later taught that economists should constantly re-examine their premises and be alert to the changing world around them.

This is not a new idea. The Chinese poet Chuang Tzu wrote in the 4th century B.C.:

How shall I talk of the sea to the frog

if he has never left his pond?

How shall I talk of the frost to the bird

of the summerland if it has never left

the land of its birth?

How shall I talk of life with the sage

if he is the prisoner of his doctrine?

I ask your indulgence for the fact that I wrote this paper more than a year ago, so the changes I tried to sketch at the end came faster and larger than I could expect in early 1973, but at least I knew then that they were likely to come.

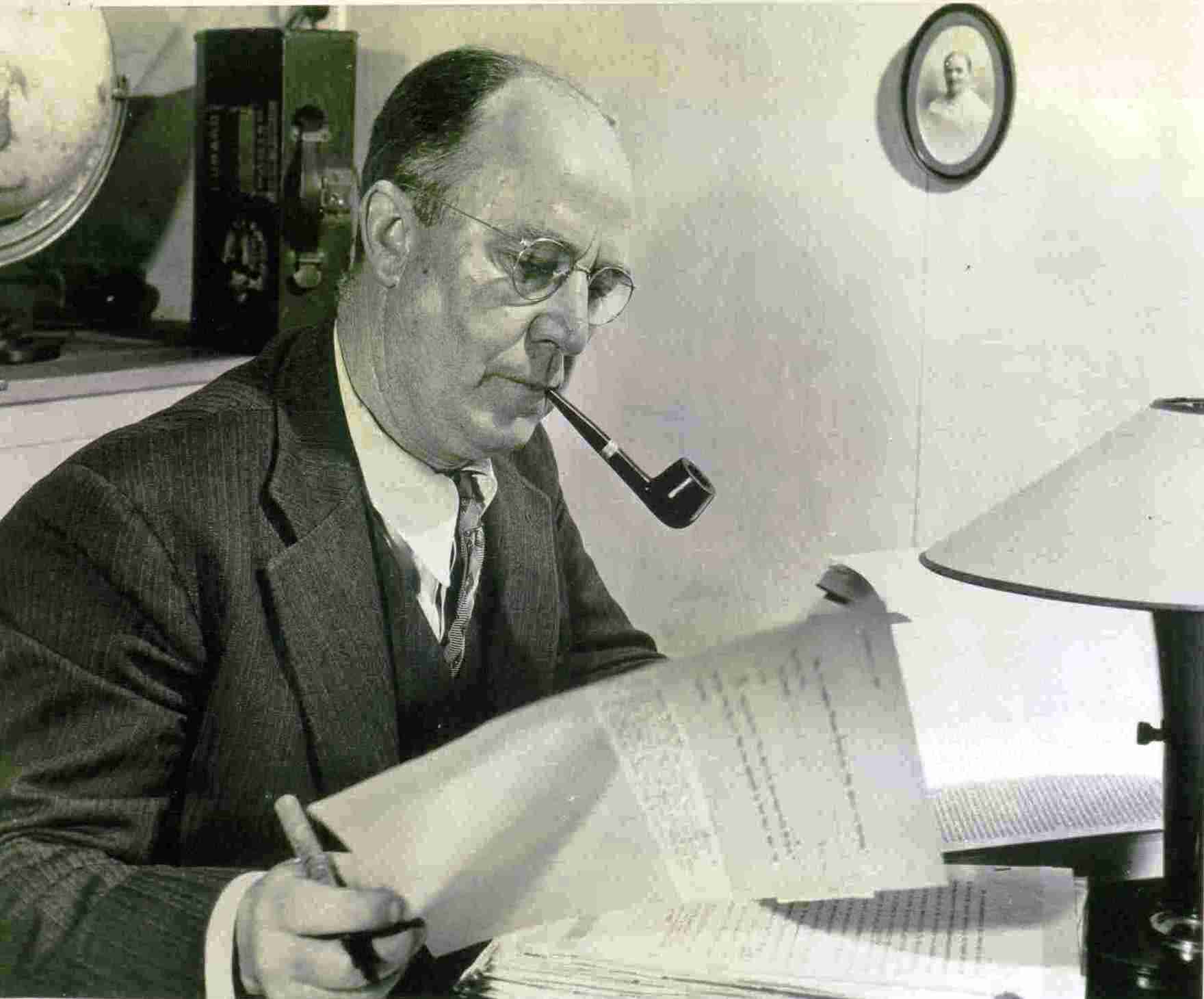

I begin with my first sight of the great economist who was one of my teachers at Cambridge.

In 1919, Alfred Marshall was still alive, living in seclusion at Cambridge. One by one his pupils came back from their war work. Keynes came from Versailles to deliver six lectures on the economic consequences of the peace. No one who heard them will ever forget that philippic directed at the policy of demanding excessive reparations from Germany. The verse he quoted from Thomas Hardy’s The Dynasts has rung in my ears ever since:

Spirit of the Years:

Observe how all wide sight and self-command

Deserts these throngs now driven to demonry

By the Immanent Unrecking.

Naught remains but vindictiveness here amid the strong

And there amid the weak, an impotent rage.

Spirit of the Pities:

Why prompts the Will so senseless-shaped a doing?

Spirit of the Years:

I have told thee that it works unwittingly,

As one possessed, not judging.

The brilliant rhetoric swept us all off our feet. Only much later, when Étienne Mantoux’s presentation of the opposing case was published after his tragic death on the last day of the second world war, did one realize how much Keynes’ argument, though valid, was exaggerated.

[Étienne Mantoux, The Carthaginian Peace, or The Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes, London, 1946]

At this time, Keynes was still an orthodox Marshallian. In 1922 he wrote:

“I do not see how one can arrive at a real stabilization except by establishing the gold standard in as many countries as possible.”

His subsequent denunciation of the return to gold in 1925 was directed primarily at the exchange level at which gold payments were resumed. In England, his attack was entitled The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill; but in the United States, it appeared as The Economic Consequences of Sterling Parity. The consequences he foresaw were unemployment at home and deficits abroad that were bound to result from a grossly over-valued currency. At that time, sterling was still the dominant world currency in which the vast bulk of international transactions was settled. It was also the currency on which most of the European currencies had been pegged, many of them after disastrous inflations. It was, therefore, the pivot of exchange equilibrium, as the dollar was after the second world war.

Keynes’ forebodings came true almost immediately. Welsh coal, then a staple export, became unsaleable on world markets. Wages were a large proportion of production costs. The coalowners attempted to reduce them. The miners resisted, and the trade union movement supported them. In 1926, there was a general strike that brought England to the verge of civil war. It was a sharp demonstration of the fact, which Keynes later emphasized in his General Theory, that organized labour would always resist any downward adjustment of nominal wages. Already in 1923, before the general strike, he had advocated public works to relieve the growing unemployment.

[J. M. Keynes, “Reconstruction in Europe,” Manchester Guardian Commercial Supplement, No. 1, April 20, 1922, p. 5]

Later, in 1930, to the consternation of most economists, he advocated tariff protection as a means not only of protecting employment in threatened industries but as an alternative to the devaluation of sterling. In the event, Britain was to suffer both protection and devaluation.

I have always thought that the decision to abandon free trade in 1931 spelled the end of Britain’s world leadership. With it went the freedom of overseas investment. Since the 1930s, many panaceas have been advocated—imperial preference, nationalization of industry, social security, centralized planning, currency devaluation, and now entry into the European Economic Community. But sterling has reeled from crisis to crisis, and Britain has never regained its self-reliant solvency in world markets.

Throughout the troubled period between the wars, Keynes continued his consistent opposition to policies of monetary deflation. Professor Austin Robinson has recently given us a vivid picture of Keynes’ incessant activity on many levels of intellectual controversy. Economists will soon have available not only his published books and the articles in many journals, which will fill four volumes, but also:

“Newspaper articles, letters to the press, contributions to the work of various committees and commissions on which he served, memoranda while in the India Office or at the Treasury, his economic correspondence.”

These writings will be printed in ten or eleven volumes. Even so, they do not cover his wide interests in the arts and the theatre, or his correspondence with his Bloomsbury friends. This was a universal man, the greatest perhaps since Adam Smith. His reputation and influence seem destined to rival if they do not surpass those of Smith.

Austin Robinson, his pupil and close associate for many years, describes him as two men: the economic statesman and the creative pioneer in economic theory—the greater in each capacity for being at the same time the other. Remembering his wide interests outside economics, one is tempted to say he was more than two men.

Despite all his interests and preoccupations, Keynes never shirked the drudgery of his economics, either in mastering masses of policy detail or in working over his theoretical formulations. Not the least interesting part of Austin Robinson’s all too brief evaluation of him is his sketch of the master at work—subjecting the first creative intuitive vision to rigorous criticism, testing, correcting, rearranging, and rewriting to achieve both accuracy and maximum impact.

It is all the more important, therefore, to be very clear as to Keynes’ own attitude toward his writings. Here again, I must quote Austin Robinson, who knew him perhaps better than almost any other economist:

“It seems to me that there are now two images of Keynesian economics. The first image sees Keynesian economics as a set of panaceas for the economic diseases of the 1930s applied uncritically to the entirely different world of the 1960s and 1970s—a belief that government policies should in all cases be expansionist and never disinflationary. In that sense,” writes Robinson, “I, and I believe many others who were his pupils and admirers, am no Keynesian. Nor do I believe that Keynes himself would have been a Keynesian.”

Keynes did consistently believe in the virtue of the highest practicable level of employment. He would always seek an alternative, if there were one, to economic adjustment by unemployment.

The second image of Keynesian economics, Robinson suggests, “is that of a system of thought in which one tries to see what are the factors influencing the propensities to consume and to save, to invest, to expand government expenditure; to see what factors are influencing and likely to influence the rate of interest; to see what is the current or expected loading of the economy and how far the elasticity of supply of output as a whole will permit expansion without more inflation than is regarded as tolerable. In that sense, almost all economists today are Keynesians—even some of Keynes’ sternest critics.”

One more quotation, and I must leave this extraordinary man and his work. Through the generations, much more will be written and spoken about him as the towering public figure of our generation, one who, in my judgment, will loom larger as the generations pass—larger even than Churchill or Roosevelt—because he has left a legacy of thought as well as action. He has already become the influential defunct economist whose ideas, diluted into slogans and catchwords, are echoed by practical men—in his case, politicians and labor leaders rather than businessmen.

Austin Robinson asks in his closing words if there were greater objectives than those Keynes set himself:

“To create a world monetary and financial system that could achieve adjustment without disaster to one of the parties to the adjustment; to create a world economy in which all countries all the time might be better able to use to the full their manpower and their resources.”

These, indeed, are lofty aims, almost utopian. The first would seem within the grasp of reasonable men. It ought to be possible to create such monetary and financial agreements that adjustments between national economies could be made without disastrous consequences to any of them. We have, in fact, come a long way towards achieving that goal. It is now more than a quarter of a century since the second world war ended. There have been strains and readjustments, but nothing comparable to the disasters that followed the first world war—no 1921 or 1929 or 1931, no runaway inflations of the major currencies, no collapse of world trade. The orthodox monetary policies followed after the first world war were the same in principle as the Ricardian policies after the Napoleonic Wars and produced the same results.

I have vivid memories of those years between the wars. In 1931, I had come to Geneva to write the World Economic Surveys summarizing and interpreting the data collected by my colleagues in the Economic Intelligence Service of the League of Nations. In one week of the first month of our stay, both the political and economic postwar settlements collapsed. The Japanese army took over Manchuria, and Britain, the pivot of the restored gold standard, suspended gold payments. The 1930s were years of incessant conferences in which the monetary and financial experts of the European countries worked to protect their own national economies rather than restore international cooperation. The United States held stiffly aloof. Month by month, the value and the volume of international trade shrank as quotas, exchange controls, and competitive currency devaluations were piled on tariffs. Sterling drifted lower against the dollar, and most other currencies went with it until, in April 1933, President Roosevelt devalued the dollar, as abruptly as President Nixon did in August 1971.

Suddenly, sterling, which had sunk nearly to three dollars, rose above five—higher than its pre-war parity.

Following what seemed to be an agreement with the United States, which was not a party to the Lausanne consultations in 1932, the League had convened a Monetary and Economic Conference to meet in London in May 1933. The outline of a possible stabilization agreement had been worked out at Geneva by meetings of experts, including eminent American economists. Per Jacobsson and I had drafted the agreement into an Annotated Agenda. Dollar devaluation in April destroyed its basis. The official conference was opened by the King, went through its organizing ceremonies, and heard a long series of opening speeches. Behind the scenes, in Claridge’s Hotel, President Roosevelt’s personal emissary, the Assistant Secretary of State, met with Keynes and others, and before long the President’s cable, deriding “so-called international bankers,” killed any hope of effective negotiations. The official conference dragged on for a few days. The Senator from Nevada was Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee of the U.S. Senate. At his request, a resolution was passed advocating a higher price for silver. This was the only result of the great international gathering. The United States could have got anything it wanted from the conference. But it was soon apparent that power lay in Washington and was expressed through the Claridge’s Hotel private meetings—a bitter lesson that the advocates of international organization find hard to learn. I was assigned to draft a brief final report of the conference, which was never printed.

By this time, Keynes was beginning to seek theoretical justification for his readiness to sacrifice the rentier capitalist rather than the unemployed. He was active behind the scenes of the conference. How much influence he exerted we may perhaps discover when his papers are published. It is probable, however, that President Roosevelt was motivated mainly by the political situation in the United States. He was never much impressed by economic arguments. The New Dealers were new in office and eager to use unorthodox measures to stem the tide of bankruptcies and unemployment.

It is difficult even now to be sure whether the failure of this last pre-war effort at stabilization was an avoidable disaster or whether the effort was premature. The chaotic international situation grew worse. Hitler also was newly in power and drew obvious encouragement from the economic weakness and political indecision of those who were soon to be confronted with his megalomania. Economic recovery was slow and in fact did not come until the free world was forced to face reality in massive rearmament programs.

Keynes published The General Theory in 1936. It was received at first with shocked incredulity by most of his contemporaries. Deliberately, he chose to shock them, being aware of the propensity in academic circles to intellectual sclerosis—hardening of the categories. Most of the younger economists capitulated immediately to his reformulated theory, and even his severest critics succumbed grudgingly. Textual exegesis now gives way to acceptance of the basic principle that there can be, and often is, static equilibrium with underemployment of resources, especially labor. Whether, without inflation, equilibrium can be continuously maintained at full employment is another question.

This leads me back to the second of Keynes’ noble objectives, which Austin Robinson phrased as:

“To create a world economy in which all countries all the time might be able to use to the full their manpower and their resources.”

“All countries all the time!” When national currencies are managed by their political leaders, who may or may not accept the advice of their experts—who in turn may or may not have the knowledge and judgment to advise wisely—and who, in any case, may think in terms of their own national welfare rather than international equilibrium! It is good to aim high. Emerson advised young men to “hitch their wagons to a star.” But in this imperfect world, our wagons bump along very earthy roads.

After the war ended in complete Allied victory, there was no Carthaginian peace, no war debts, and no reparations. The United States emerged as the strongest economic power and the only source of capital for reconstruction. It had been the mobilizing center of the war effort and had reaped the military and industrial rewards of international cooperation. From 1946 to 1958, it was in a position to dictate military, political, and economic policy to allied and enemy countries alike. It chose instead to use its resources to restore international cooperation. How far Keynes should be credited with persuading President Roosevelt and his administration to follow such enlightened policies, we may never know. It is possible that the Full Employment Act of 1946 was passed by Congress without full realization of its revolutionary import, but it was a remarkable tribute to the influence of his ideas. Public opinion in America, however, was in a generous mood of buoyant optimism.

Immense resources were poured into the reconstruction of the defeated enemy countries. Not least important, it now becomes apparent, were the low parities at which both Germany and Japan were helped to restore their currencies. The vast gold reserves that had accumulated in the United States were redistributed in the course of reconstruction, trade, and investment. It became possible to create new international monetary and financial institutions.

Keynes had written a special preface for the German and Japanese translations of his Treatise on Money. In it, he made clear that his main concern in this, the most academic of all his writings, was:

“to develop thinking about a gradual evolution of a managed world currency in conditions in which he was convinced that the traditional gold standard was likely to become increasingly unworkable.”

We are now grappling with this evolution of a managed world currency. For the first time in history, we are attempting to create a truly international currency system in which no single national currency is dominant—not a sterling standard or a dollar standard but an international standard with an international paper unit as the pivot. And a managed standard at that, not tied to gold, sterling, or the dollar, but managed by cooperation and compromise among the national monetary authorities of the world. This, if successful, would be an installment of world government in the most important segment of economic policy.

Who would manage it? We already have some experiments in world government in technical fields where the common interest transcends the national—in postal and satellite communication, in air traffic, in communicable diseases, narcotics, refugee placement, labor legislation, and agriculture. These experiments vary in effectiveness. The more they touch economic interests, the less effective they are. The United Nations is far from realizing Tennyson’s dream that:

“There the common sense of most shall hold a fretful realm in awe

And the kindly earth shall slumber, lapt in universal law.”

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund are sui generis, in the sense that they are endowed with their own funds and not dependent on annual appropriations. But on the great matters of policy, they remain under the firm control of national governments, weighted by their contributions. Until recently, the United States’ share was so large that it could, if need be, exercise a veto power. Now this veto power can also be exercised by the European Economic Community. So the technical experts appointed to draw up plans for improved monetary arrangements formed the Committee of Ten, representing the great industrial and creditor powers. That Japan was a member is a significant fact, portending change. The Ten became Eleven when Switzerland participated, and now they are Twenty, with some representation of the smaller countries. The poorer countries of the world can at least have their viewpoint expressed. But power still rests in the governing board of the Fund and effectively in the national monetary authorities of the great powers, which have never hesitated to devalue their currencies or restrict imports when they deemed this essential in the national interest.

The expert secretariat of the Fund, under strong leadership, can indeed be regarded almost as the equivalent of a great power. Per Jacobsson did build the Fund’s status to this point, but when his equally able successor expressed views that displeased the American authorities, he seems to have done so at the cost of his own position. So we cannot ignore the immense power of nationalism. The difficulties in creating effective international arrangements for monetary cooperation are not technical or economic, but political.

It is for this reason that economic theories basing their analyses on closed national economies need to review their assumptions. Keynes set a pattern when he chose in the General Theory to ignore the international repercussions of his argument and went out of his way to praise the Mercantilists. Calculations of Gross National Product count imports as leakages of national income. Even if his posthumous article had not stressed “the permanent truths of great significance” in the classical teaching, the time and effort Keynes contributed to the creation of the Fund and the Bank are proof enough of the importance he really attached to international economic cooperation. If his too-literal followers continue to focus their analysis on the assumption of closed national economies, it may come to be said of him, as it was of Caesar:

“The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones.”

The emergence of Japan as a great industrial, financial, and monetary power gives evidence that the world we are entering will be vastly different from that which Ricardo, Marshall, and even Keynes took as the basis for their reasoning. It is easy to talk of the peoples of the world and fatally easy to personify them by countries. In fact, the concepts of nationalism and national sovereignty are undergoing radical change, primarily for economic reasons.

In a world that uses up its limited natural resources so rapidly and so recklessly, even the greatest industrial power must take heed to the economic structure it builds. The world now uses more petroleum in less than a decade than in all previous history. The doubling periods for a long list of basic minerals are almost equally short. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Jevons drew attention to the imminent depletion of Britain’s coal resources. Improved methods of extraction put off the evil day, but coal is a dying industry. It is dying also in Germany. One could go through a long list of minerals in which the leading industrial countries are now, or soon will be, deficient. Japan, the most deficient of all, has nevertheless attained its present power by using the newest techniques of ocean transport to acquire cheap raw materials from all over the world. Proximity to raw materials is no longer a deciding factor or even an advantage in the location of industry. Nor is what Alfred Marshall called “the momentum of an early start.” The theory of industrial location must be revised. The cheapening of bulk transport is still going on. With it goes the construction of pipelines, which can now carry not only liquids but solids suspended in liquid, over land and under the sea. Riverports and even harbors all over the world are being bypassed by the huge floating carriers that tie up at ocean terminals and pump their cargoes ashore.

The multinational corporations that have taken advantage of such new methods are made possible by recent developments in electronic communication, now linked with even more fantastic methods of electronic calculation. These developments change the focus of power. Ownership of capital becomes less important as it is dispersed among very large numbers of absentee shareholders whose control over management is indirect and often minimal. The power of decision passes to those who achieve dominant positions in management. Policy is still approved in principle by boards of directors who are nominally elected by shareholders but in fact selected by management, often from among their own colleagues. Executive management in detail is delegated. In the most successful of the new industries, the upward mobility both of men and of ideas becomes a major objective of senior management. This mobility spreads across national boundaries.

The new multinational corporations that are pioneering these developments have recently been compared with the Elizabethan joint-stock companies such as the East India Company; but the comparison is very superficial. One example must suffice to illustrate this and to indicate how the newest developments are changing the basic economic assumptions on which economic theory must be based.

When petroleum was located beneath the sands and the seas of the Middle Eastern deserts, most of the local population of the almost unknown deserts of Saudi Arabia were illiterate, migratory peasants ruled by tribal chiefs. Their claim to ownership was not disputed or ignored as it would certainly have been by an Elizabethan company. An agreement was signed with Ibn Saud, who had just begun to extend his rule over the whole country. This agreement, and the increasing royalties as oil production increased, helped to consolidate the kingdom.

Under the guidance of a remarkable American—son and grandson of missionaries, diplomat, soldier, and Arabic scholar—the foreign technicians who came to Saudi Arabia were trained and disciplined against any infringement of Arab laws and customs. Local labor was recruited and trained. My wife and I happened to be in Dhahran when the famous 50-50 royalty agreement was signed. Royalties have steadily mounted to fabulous sums. Within a few years, the Arab government may be receiving twenty billion dollars a year and will have about thirty billion dollars of foreign exchange reserves. There are now several hundreds of thousands of Arabs who have been trained in the company schools. Many have set up in business for themselves. Many have gone on to secondary schools and universities, and a substantial number have risen to management rank in the company. Very recently, an agreement has been reached by which the government will acquire ownership of the company, beginning at 25 percent and rising in a relatively short time to 51 percent.

The young Arab minister who negotiated this agreement, not only for Saudi Arabia but for Kuwait, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Iraq, has now made a public offer to negotiate with the United States an agreement to meet the growing petroleum shortage by supplying crude petroleum and investing Arab capital in the refining and distribution of petroleum products in the United States. We are already aware of Japanese investments in Hawaiian hotels, Australian mines, New Zealand timber yards, Latin-American, and North American industries. It will not be long before other newcomers, such as the Saudi Arabs, will spread their investments to varied enterprises all over the world. The Shah of Iran is demanding an agreement with the international oil companies better than the Arab countries received. Those countries that control essential raw materials and oil will be the rich and powerful peoples of the next generation. It was a mistake for economists to neglect real assets by making all their calculations in purely monetary terms.

The consumption of petroleum is so great and increases so fast that the United States is threatened with a severe shortage. Its domestic reserves begin to fail, and such overseas producers as Venezuela and Kuwait already foresee the end of their supplies. So negotiations are underway to find new sources of supply. Plans are far advanced for Japanese and American ventures, in cooperation and individually, to tap the natural gas of inland Siberia, bring it by pipeline to the Pacific Coast, and ship it frozen into liquid in special cryogenic tankers.

This is no longer a European or an American-dominated world. It is possible that it may cease to be as national a world as we have known it. For good or ill, Britain has thrown in its lot with Europe. The European Economic Community has become the largest economic group in the world, larger than the Soviet bloc or the United States. Japanese economists and some business groups are beginning to explore the possibility of a Pacific economic community.

The units of political organization are changing their character. Inevitably, the influence of the new groupings extends over neighboring areas. The Mediterranean and African countries become a sort of European hinterland. The Japanese would welcome American cooperation in developing Southeast Asia. The Russians extend their influence south and east. Chinese diplomacy is active in parts of Africa. No one can yet foresee the shape the political world will take by the end of this century.

Nor can one foresee how the new multinational forms of business organization will develop. They may encounter the fate that has already overtaken some of them in Chile and Peru. Or they may develop new and powerful forms of economic cooperation, as the Saudi minister has foreshadowed. They will undoubtedly play a large and perhaps decisive role in future international agreements. If, for example, Arab influence were to increase in international monetary negotiations, it seems likely to me that they may have more confidence in gold than in Mr. Connally or Mr. Schulz, or any other advocate of managed currencies.

One fact is very clear: Monetary and balance of payments problems can no longer be thought of in simple terms. They are shifting complexes of trade, investment, transport, market regulation by industry and government, fluctuating exchange rates, and interest rates determined by national rather than international considerations. Simple models of economic development, assuming no international trade and no government interference, cannot throw much light on the prospects of national development or decline.

Some legacies of the past remain to be liquidated. The overhang of sterling balances and the dollars—now estimated at 60 billion—that fuel speculative movements in the foreign exchange market must be funded and written down or off. The swap arrangements between central banks must be tidied up before realistic parities can be agreed on and kept. The sooner, the better. The longer currencies float or are subject to speculative attack, the more protective barriers are raised to international transactions, and the greater becomes the danger of another worldwide collapse.

I do not pretend to know what can and should be done. The answers must be found by younger economists who do not suffer from a hardening, even of the Keynesian categories. They will need all the wisdom they can draw from Keynes and from his predecessors; but they will need still more the courage and realism to face the facts as they find them.