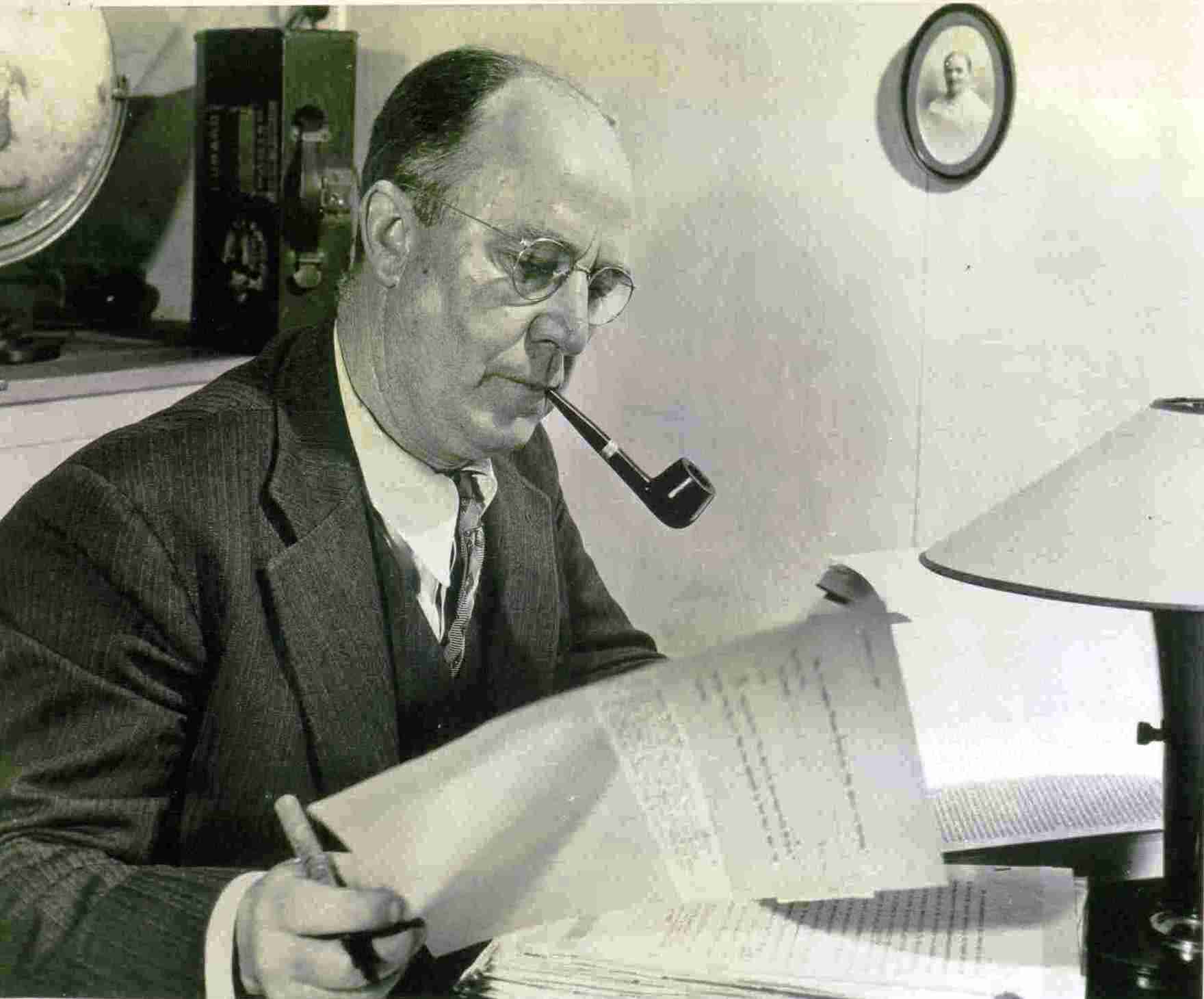

Introducing Jack Condliffe

John Bell Condliffe, born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1891, moved to New Zealand at an early age. Nevertheless, his wife Olive, who is a New Zealander by birth, sometimes refers to him as “that Australian.” However, he became a citizen of the United States in 1945. Jack attended the University of New Zealand at Christchurch, where he received a Bachelor’s degree in 1914 and a Master’s, with first class honors in economics, the following year. But quite as important, he played on the Canterbury College rugby team. His studies were interrupted when New Zealanders enlisted for the war in Europe. Jack took his place among them as a private in the infantry. He continued to play football while in training and participated in a game with a British naval team led by Lord Louis Mountbatten. How we wish we had a movie of that action! The New Zealanders went to the Western Front and Jack was in the thick of it until, in February 1918, he was severely wounded and sent to England for hospitalization. Upon recovery, he was given a fellowship at Gonville & Caius College at Cambridge for a year before returning to New Zealand to become Professor of Economics at Canterbury University College, where he remained for six years.

His reputation soon became international. He was successively Research Secretary for the Institute of Pacific Relations at Honolulu, Professor of Economics at the University of Michigan, member of the Economics Intelligence Service of the League of Nations Secretariat in Geneva, and Professor of Commerce at the University of London. At last, in 1940, he came to roost in Berkeley as Professor of Economics at the University of California. However, J. B. Condliffe was never the man to stay tied to one spot. From time to time, he flew the coop to be Assistant Director of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in New York; Consultant to the Board of Economic Warfare in Washington; Consultant to the National Bank of Mexico in Mexico City; and Visiting Professor of Economics at Yale. That is not all: on leave from Berkeley, he managed to get around even more widely as Visiting Professor in Australia, in India, and at Beirut. In 1951, he was a Fulbright Professor at his old college in Cambridge, England, then Consultant to the Ford Foundation in New York.

One might suppose the Professor would be glad to settle down in the dignity of Emeritus upon the conclusion of his professorship at Berkeley. Hardly. First, he spent a year in India as Advisor to the Indian Council of Economic Research. After that, he did indeed settle down, as Senior Economist and Director of Basic Economic Research at Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park. But even that involved a little excursion. He went to Australia to produce a report on “The Development of Australia,” published in 1964.

Perhaps the most popular of Condliffe’s publications are his historical and economic works on New Zealand. In 1959, he brought them up to date with The Welfare State in New Zealand. He has been frequently honored. Besides honorary doctorates from the University of New Zealand and from Occidental College, California, he has received the Henry E. Howland Prize from Yale University “for creative achievement of marked distinction,” and the Wendell L. Willkie Prize of the American Political Science Association “for the Best International Book of the Year” — The Commerce of Nations, 1950. He received from Greece, in 1955, the Royal Order of Phoenix. The list of his associations with professional societies is extensive.

Over and above all these distinctions, Jack Condliffe is a Bohemian. He joined the Club as a faculty member in 1953, and in 1958 became a member of Silverado Squatters Camp. His genial companionship and stimulating conversation have enriched Grove Encampments and many other gatherings of Bohemians. The vast experience depicted in this introduction is reflected in the following essay, which he presented at a Lakeside talk at the Grove in 1964.

— Francis P. Farquhar

From Adam Smith to Keynes & After

Forty-eight hours ago, Clarence came to Silverado to put me on this spot. I was barely awake—just out of the shower. I’m not sure his idea was a good one—one New Zealander after another and two Squatters in a row, but I rose like a trout and was hooked. I’m sorry about the unpronounceable title—it was the best I could do when I was caught naked—no time to reflect and no books to consult. But the title doesn’t mean any more than a political platform. It’s made to get in from, not to run on. What I want to talk about is the influence of academic economic theory on the world of action.

This is a subject upon which you are all experts. There is only one other subject that has such universal appeal. Adam was tempted by Eve and he has had to keep her ever since—by the sweat of his brow. A good deal of the conversation in the Grove revolves around these two themes—sex and sweat—and most of it is theoretical. When I hear sly references to Monte Rio, the words of the old spiritual come back to my mind—“everybody talkin’ about heaven ain’t going there.”

It is just the same with the economic theory behind the political arguments and business talk. Keynes ended his great book with some paragraphs arguing that ideas were the most powerful forces in the world. The practical man who is impatient with theory in fact derives his own theory from the ideas of some defunct economist. I hear the ideas of these defunct economists echoing all over the Grove—like the voices out of the past that come echoing back to us at the Old Guard dinner. Don’t misunderstand me—I like to hear these echoes. I have heard it argued that the difference between a politician and a statesman is that a statesman is a dead politician—and what the world needs is more statesmen. It has been said that if all the economists in the world today were laid end to end, they would reach no conclusion. Maybe an economist has to be defunct before he can exercise much influence. At least the men I’m going to talk about had ideas, and these ideas have been influential in shaping our world.

Adam Smith and His Legacy

I start with Adam Smith, not because he was the first political economist, but because he was a philosopher, and in any case, I like his ideas. He was a very practical, down-to-earth Scot, as you may read on every page of his Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. What he says in his very first sentence is that the wealth of a nation is determined by the combined labor of all its people. Then he goes on to describe the division of labor in making a pin. These practical observations are found throughout his work. He met regularly with the merchants who formed the first Chamber of Commerce in the city of Glasgow. When the trade union local wouldn’t let James Watt ply his trade in the city, Adam Smith found space in the University for his experiments on steam. In his later life, Adam Smith was Commissioner of Customs. His powerful argument for free trade is reinforced by very practical examples of the inefficiency of the protective Mercantile System.

So here is a philosopher concerned with broad questions of principle, but not content to leave them in the air. He strove always to apply them to the working world of his day, and he could do this with a sure touch because he took pains to study what was actually going on.

Moreover, he wrote in English that anyone can understand and enjoy, and he had no illusion that economics could be separated from politics. To my mind, it is unfortunate that political economy, which used to be written by Scotsmen in English, has now become the pseudo-science of economics, written by Hungarians in mathematics.

Malthus, Ricardo, and Marx

Before I come to Keynes, I must mention briefly some others who emerged to influence the course of history with their economic ideas. First, there was a prophetic clergyman—the Reverend Thomas Henry Malthus—who published in 1798 an essay on population which ought to be compulsory reading today. Malthus was the first Professor of Political Economy—Adam Smith’s chair was, and still is, Moral Philosophy. Malthus was appointed at Haileybury College by the East India Company to train the men they were sending out to India. It is very unfortunate that he lost out in his long-continued debate with his contemporaries in the early years of the nineteenth century.

This, you will remember, was the period of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. England fought France on and off for more than twenty years, and refugees from all over Europe fled to this island fortress of liberty. Among them were the parents of David Ricardo, who was expelled from his family when he married an English girl. Some friends set him up as a stockbroker—in those days, government securities went up and down violently with every victory or defeat in the wars. Ricardo made enough money out of these fluctuations to retire by the time he was twenty-five. This, of course, made him an authority on money, and eventually, in 1823, he produced a book on The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. I defy you to read this book. Unlike The Wealth of Nations, it is highly abstract deductive reasoning with virtually no practical illustrations. Political economy became a series of abstract financial propositions expressed in tortured English. Above all others, Ricardo’s work fits the definition of economics as common sense made difficult.

I suppose few leaders of industry ever read Ricardo, even in his own time, but he became the economists’ economist, and two of his disciples later exerted an enormous influence on events.

The first was John Stuart Mill, whose Principles first appeared in 1848 and was still used as a textbook when I was a student. The second was Karl Marx, who wrote the Communist Manifesto in that same year, 1848. John Stuart Mill was an infant prodigy whose father was an intimate friend of Ricardo’s. All his life, he was haunted by the fear of tuberculosis—a good illustration of Dr. Robbins’ argument at the Lakeside on Tuesday. His father began to teach him Greek at the age of three, and Latin at seven, logic at twelve, and before he was thirteen, he had to repeat each day to his father the argument of a proposition in the textbook on political economy that the old man was writing on Ricardian principles. With such a father and the fear of tuberculosis on his mind, he was bound to break out somewhere. When he was a young man, he was picked up by the London cops for distributing obscene literature in the form of birth control pamphlets. Then he met a lady who was already married and began what seems to have been a purely platonic but very intimate relationship with her until her husband died, and they could marry. It was this lady, Harriet Taylor, who turned Mill into the paths of philosophical liberalism. She is the “true author and only begetter” of the welfare state, which is essentially feminine in its concept and practices.

What Karl Marx did I needn’t elaborate. He stood Ricardian reasoning on its head to develop the labor theory of value and all the other theses of class war and revolutionary communism. The communists still regard Ricardo as the founder of scientific economics.

I cite these two cases to show what can happen when an economist loses touch with the actual work of the world and gets himself involved in theoretical abstractions. The basic economic reality is, and always has been, the truth expressed in Adam Smith’s first sentence—the income of any nation comes from the work of all its people—all kinds of people—the laborer in field and factory, the research scientist, the artist and musician, and not least the organizing executive manager. Whenever we lose sight of this reality and become so involved in our transactions that we don’t expose them to the acid tests of practical application, we run a grave risk of ending up in the authoritarian camp.

Mathematical Economics and Alfred Marshall

In the middle of the nineteenth century, some mathematicians began to apply the calculus first to the theory of marginal utility and then to other aspects of economic behavior. No one can deny that the precision of mathematical analysis is the most powerful tool ever invented by man. But human behavior is apt to escape from the calculus. The mathematical economists are bothered by this, so they leave this imponderable human element out of their equations. This bothers me. When, as a very raw student, I took out from the college library the first book I ever read on mathematical economics, the old librarian held the book in his hand and said to me: “My boy, if you borrow this book, you should not just glance through it and bring it back to me. You should read it thoroughly and digest it. But when you have done this, I beg you to remember that (a + b)² = a² + 2ab + b² only on one condition—that a is not stronger-minded than b. If he is, the result will be a³ + b.”

I was brought up on the textbook of the great Cambridge teacher, Alfred Marshall, who first put economic theory into a comprehensive and tidy mathematical framework. In a letter to one of his pupils who later succeeded him as professor and was my tutor at Cambridge, Marshall suggested four rules for the use of mathematics. First: work your mathematics out completely and be sure they are correct. Second: find important examples in real economic life for every mathematical term you use. Third: translate into English. Fourth: if you can’t find important realistic examples, burn your mathematics.

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes was Marshall’s most famous pupil—both of them were Wranglers, and Keynes’s first work was on the Theory of Probability. But there is a clue to Keynes that is often overlooked. His mother, a great lady who was Mayor of Cambridge for many years, was a daughter of the Baptist parson who wrote the authoritative life of John Bunyan. Through all his artistry and sophistication, there was a nonconformist, evangelistic streak in Keynes. Like all great economists, he was a pamphleteer—the greatest in England since Swift.

Arnold Toynbee—not the current exponent of circular historical reasoning, but his uncle—once wrote that “while affecting the serious and reserved air of students, economists are all the time to be found brawling in the marketplace.” They always have a belief to proclaim, a policy to advocate, a cause to promote. Even when they are being most scientific in precise mathematical language, their beliefs creep into their assumptions and definitions. Adam Smith preached free trade and the virtues of competition, Ricardo advocated hard money. Keynes wrote a great book which he called The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, but what he was concerned with was the massive unemployment that seemed incurable in England during the Great Depression. If he had lived longer, he would have been off on another tack. He was annoyed by the Keynesians who treated his writings as if they were Holy Writ. When one of them reproached him with inconsistency, his reply was devastating—”the difference between you and me,” he said, “is that I’m not a Keynesian.”

American Economists and the Influence of Economic Theory

I have two more things to say, but first I must explain why I have not mentioned any American economists. The reason is that economic theory as it is taught in the United States is almost wholly derivative—a curious hangover of the colonial inferiority complex. When I wrote The Commerce of Nations, I found all the references to British and European sources in the University Library, but I had to go to the Congressional Library for the American literature I needed. There have been heretical economists in America—Alexander Hamilton, Veblen, Henry George—but their ideas don’t get into the textbooks. What is even more curious is that you will not find in the accepted textbooks much reference to the men whose enterprise created the most productive economy the world has ever seen. You will find the names of such people as Henry Ford, Du Pont, Rockefeller, Carnegie, Gary, and Sloan in the anti-trust literature, but not in the textbooks of economic principles.

It is true, of course, that these men were not interested in economic theory. I had a good illustration of this when, in filial piety, I ordered from a catalog a first edition of Alfred Marshall’s Principles. It came to me with Andrew Carnegie’s bookplate—I would have said uncut, but Warren Howell tells me the correct word is unopened. One reason why the lessons of economic enterprise in the United States do not find their way into the textbooks is that academic economists take their ideas from abroad and seldom have much direct knowledge of American business methods. Until recently, the leaders of business enterprises haven’t bothered much about introducing academic economists to the facts of life. I suggest to you that this has been a mistake. You may think we professors are a bunch of crackpots, but we teach the young people who in this democracy of ours will take your places in a generation or so and will vote long before then. They will echo our ideas as you echo the ideas of our defunct predecessors.

If economists haven’t had much influence on business in recent years, they have had on government. Since Keynes, all textbooks are written in monetary terms. Real value, real cost, and all the realities of economic organization are gathered up in averages and aggregates—National Income, Gross National Product, Coefficients of Capital, Production Functions, and the like. All these ought to be taken with a grain of salt. If you want to increase the G.N.P. right now, you should all put your wives on a salaried basis and pay them the half of your income they are entitled to anyway under the community property law.

The result of these monetary calculations is that when action is sought—to remedy unemployment, to promote research, or to accelerate economic growth—it is thought of in aggregate and usually monetary terms and by government. The great problems of our day cannot in fact be solved in the aggregate or by political manipulation of credit and fiscal policy. They are primarily structural. What can we do with our cities? With the growing numbers of people who are not equipped to work effectively in our mechanized and computerized economy? How shall we prepare our people to make constructive use of their leisure and of their retirement years? We need a new economic philosophy more than we need more highways and more automobiles to create the need for still more highways and to destroy more redwoods. Even in the Grove, the traffic problem gets worse every year.

Monetary Expansion and Global Risks

And so I come to my postscript—”and after.” Because we have come to believe that governments can solve all economic and social problems by creating more credit, we have financed one of the longest periods of monetary expansion in history—not only here, but all over the world. First, we wrote off the lend-lease obligation of our allies—this was sensible. Since then, we have spent about 100 billion dollars—putting Europe on its feet again, and Japan; and now we are attempting to develop the 70 percent or more of the world’s people who live at levels below $200 a year—most of them far below. We have given up the gold which came here during the war and have built up formidable short-term obligations in the form of dollar holdings abroad. This drain has now reached the point where we must watch our balance of payments lest our foreign creditors lose confidence in the dollar.

How much longer can this credit expansion go on? The answer is quite simple, but not very conclusive. It can go on as long as the monetary authorities in the great trading nations can keep the expansion going at the same rate in every country—or, as the engineers would say, in parallel—so that sudden strains on the balance of payments, including our own, do not become unmanageable. Inflation, of course, is already out of control in many of the less firmly governed countries—the Argentine, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, and others. This doesn’t matter so much. What is more ominous is the situation in Europe—in Denmark, France, Italy, and perhaps soon in Britain if there is a massive flight of capital from a socialist government.

Large monetary reserves are available, but more and more they consist of credit extended among themselves by the central banks. So their use depends on prompt and cooperative action agreed upon between the Europeans, the British, and ourselves. How much longer can we count on such cooperation? Your guess is as good as mine. But 1964 looks to me very much like 1928, just after the French had devalued and were piling up gold, when installment sales were booming and real estate was going up. The stock market hadn’t then taken off into orbit, but it was already on the launching pad.

It went into orbit, you will remember, after the Governor of the Bank of England came over to plead with the Federal Reserve System not to put the brakes on for fear of precipitating a collapse in Europe.

It seems to me that we are running some risks and ought to be careful. Three years after 1928, when I had just written the first World Economic Survey for the League of Nations, an American banker asked me what the root cause of the trouble was. I told him: “Oh, you American bankers lent these people too much money.” I have never forgotten his reply: “I suppose you are right, but I made many of these loans myself and every loan I made was sound at the time and in the circumstances when I made it. How was I to know that in the aggregate all the loans would be unsound?”

Development Challenges in Underdeveloped Countries

What do we get for running such risks? One thing is sure: there are more people in the world and more to come, many more. Three-quarters of the increase will be in the underdeveloped countries. There are some economists who predict that many of these countries, including India, are close to “taking off” into self-sustained economic growth. I use the language of the economic historian who is currently Chairman of the Planning Committee of the State Department. But I remember the title of a British pamphlet published during the war, and personally I have “some doubts as to the imminence of the millennium.”

The reason for my doubts is the theme of this talk. We started this development business at the wrong end—misled by the economists who forgot that wealth is created by people and argued that massive injections of capital could industrialize people who have never learned to connect cause with effect and don’t believe it when you tell them—like the villagers in India who refused to use the water from a huge power project because all the electricity had been taken out of it. We were not the only ones who were misled. Generations of foreign students who are now governing their countries were taught these fallacies in our universities.

We have never used the economic muscle that has made the United States so productive—the technology, know-how, and managerial experience of our private enterprise system. When we send out a government mission or a technical expert, we get a report. I know. I’ve been sent out.

If a business corporation sends out a mission, you may not get as polished a report, but finished products are likely to start coming off the assembly line. In these undeveloped countries, sergeants become generals, clerks become ministers. You will find steel plants run by civil servants and planning commissions full of Ph.D.s trained in economic theory who can make wonderful econometric projections. But you won’t find many managers who’ve come up the hard way and whose judgment has been tempered by experience and responsibility.

If government would concentrate on creating conditions in which corporate enterprise and technology could go to work, we could lick this problem. It would take a long time, but it could be done. Think of the mass market in India alone, if organized research was put to work on designing very simple, sturdy, and cheap implements and consumer products. The Japanese begin to do this. They produce a plastic rice bowl about a third of the cost of pottery or brass bowls. What Henry Ford did with the Model T could be repeated in a thousand forms. But all the money we and the Europeans pour in—over a billion dollars this year to India alone—will never achieve real development unless know-how and industrial experience control the use of this money.

Conclusion

So I come to my conclusion. You may not think much of economic theory and still less of economic theorists; but they should not be underestimated. What we theorists teach our students, they will put into practice much more quickly than in the past. It was seventy years before the British Parliament put Adam Smith’s free-trade ideas into law, but Keynes wrote his General Theory in 1936, and the United States Congress passed the Full Employment Act just ten years later. It might not be a bad idea to take some trouble to educate the academics in the facts of economic life, so what they teach the future voters, if not future business leaders, will take more account of the values and the experience that have made this country the force that it is in the world.

Written by John B. Condliffe and printed by Edwin Grabhorn for presentation to Friends in Bohemia by the Silverado Squatters: William Bark, Kenneth K. Bechtel, John B. Condliffe, Francis P. Farquhar, Edwin Grabhorn, Clifford V. Heimbucher, Deane W. Malott, Garfield D. Merner, Franklin D. Murphy, David Packard, G. Baltzer Peterson, Alexis E. Post, Philip H. Rhinelander, Francis M. Wheat