University of California, San Francisco

For the genial members of the Chit-Chat Club, San Francisco, at their dinner meeting, Monday, February 8, 1971

The word “sterling” symbolizes quality in silver or in character. It derives from an old English term, “steorling,” a coin with a star, since the early Norman silver pennies showed a star. The pound sterling was a pound weight of silver pennies, and the word “sterling” came to mean money of the same quality or standard as genuine English money. Thus, “sterling” gradually acquired the meaning of standard or high quality, and thus of character, principles, occasionally (as the Oxford English Dictionary has it) of people.

Perhaps this derivation of the word “sterling” is fitting to one who carried it as his name, precious to him indeed. George Sterling, author, born in Sag Harbor, on Long Island, New York, December 1, 1869, son of George Ansel and Mary Parker (Havens) Sterling; died November 18, 1926, in San Francisco.

The Criteria of Poetry

Robert Graves is a remarkable writer. Now in his seventies, he continues to startle with his prose and poetry. The latter, he says, has been his ruling passion since he was fifteen years old. His poetic skill was properly acknowledged when he was invited to become professor of poetry at Oxford in 1960. This was an unusual honor, since he had repeatedly expressed his scorn for conventional English versifying, written, as he said, by gleemen, not poets.

Robert Graves, in his brilliant tour de force, The White Goddess, agrees with the Welsh poet, Alun Lewis, who wrote, just before dying in Burma in 1944, of “the single poetic theme of Life and Death…the question of what survives of the beloved.” The reader of a poem faithful to this theme is affected with a strange feeling, between delight and horror, of which the physical effect is that the hairs stand on end. A.E. Housman also used this test as a criterion for a true poem.

The theme, according to Graves, is the antique mythological story of one’s birth, life, death, and resurrection, as exemplified by the God of the Waxing Year in his losing battle with the God of the Waning Year for the love of the capricious and all-powerful Three-fold White Goddess, their Mother, Bride, and Burier. The real poet, says Graves, identifies himself with the God of the Waxing Year and his Muse with the Goddess; the rival is his blood brother, his other self, the dark God of the Waning Year.

The Goddess is envisioned, continues Graves, as a lovely, slender woman, with a deathly pale face, lips as red as rowan-berries, startling blue eyes, and long dark hair, who can assume many shapes—from serpent, mare, tigress, or mermaid to loathsome old hag.

On taking the Oxford Chair of Poetry in 1960, Graves wrote, for the Atlantic Monthly, from his home on Majorca, a series of poems, entitled “Symptoms of Love,” prefaced by a typical essay on “Service to the Muse.” One of these poems may serve to illustrate what he was talking about:

Going confidently into the garden

Where she made much of you four hours ago,

You find another person in her seat.

If your scalp crawls and your eyes prick at sight

Of her white motionless face and folded hands,

Framed in such thunderclouds of sorrow,

Give her no word of comfort, man,

Dissemble your own anguish,

Withdraw in silence, gaze averted—

This is the dark edge of her double-axe:

Divine mourning for what cannot be.

As Graves insists, the true poet knows the full background of every word he uses, its source, development, and burden of mythological and historical allusion. By these criteria, stated so defiantly by Robert Graves, George Sterling was a true poet. In his antique ballad, The Witch, he invokes the Muse in much the same words as Graves used to describe Her:

Erik the prince came back from sea,

His galley low with spoil—

Armor and silks and weeping slaves,

Silver and wine and oil.

And there was one that did not weep,

But laughed in Erik’s face,

And ‘tween the helmsman and the mast

Strode with a leopard’s grace.

Her hair was darker than the night

In which our foemen sink;

Her limbs were whiter than the milk

Of which our maidens drink.

Her lips were coral-red; her eyes

As shoaling seas were green.

She wore cupped gold on either breast

And one blue gem between.

Sterling was capable of deep emotion. Nevertheless, he sought companionship and understanding, and found a bit of it in San Francisco.

An account of him is given by Gertrude Atherton in My San Francisco: A Wayward Biography (The Bobbs-Merrill Co., Indianapolis, 1946, pp. 98-101).

“Bierce, Charles Warren Stoddard, Mencken, Robinson Jeffers, and many others have proclaimed George Sterling a great poet… Whether time will award him the laurel wreath or not, I am glad he was acclaimed as great during his lifetime, for, modest as he was, it must have given him many thrills of pleasure—although, since he had a sense of humor, I am willing to wager his mind rippled with laughter as he stood before the architrave of the Panama-Pacific Exposition and read those deeply carved lines of poetry signed Shakespeare, Milton, Sterling. But great or not, he was a serious poet, and would have sacrificed life itself for his Muse.”

Of his eighteen volumes, thirteen were published by Alexander Robertson. There was no second edition: the demand for poetry was limited then as now, but, although the sales were confined to California, many of his poems were republished in Eastern magazines and newspapers, and in 1925 Henry Holt brought out a small volume of his shorter poems. (Macmillan later published his dramatic poem, Lilith.)

He was always poor, but money was the last thing he thought of—except when some other indigent writer asked for a loan, and then he either begged or borrowed to supply the need greater than his own. For many years, he gave his services without remuneration to his friend, Miss Virginia Lee, editor of the Overland Monthly, and even induced such eminent poets as Robinson Jeffers and Edgar Lee Masters to write for it, to say nothing of lesser poets and writers of fiction now for the most part forgotten, but popular in their day.

If he had inherited a fortune, he would have given it away, and he was no less prodigal of his time. Miss Lee relates that “he reviewed over six hundred volumes of poetry for an amazingly large group of tiny publications scattered over the country.” He reviewed prose work for the newspapers, and just before his death a miscellaneous assortment of volumes for the Overland Monthly. He is the author of seventy-odd short stories and a tremendous amount of variously-sized prose sketches in the Carmel Pine Cone and the New York Times. Newspapers, menus, catalogues, fair bulletins, anthologies, pamphlets, magazines, book forewords, parades, public campaigns—he wrote everything from hymns to advertising. Every committee started in San Francisco wanted something from him to aid their cause. Friends with the autograph phobia, little poetry magazines, motion-picture magazines, and druggist pamphlets—all extracted some contribution from the author of Testimony of the Suns.

An appalling waste of a poet’s time. But it serves to emphasize his immense popularity and importance. He also had other demands upon his time. Women ran after him, and perhaps he loved too many. He was also extremely convivial, sometimes to the point of dissipation.

I met him several times at Montalvo, Mr. Phelan’s country place. He was the ideal poet in appearance, tall, gracefully built, with a mop of dark hair that fell over his forehead (but properly cut), large gray eyes “that had an eternally burning softness,” and a beautifully curved mouth, which was generally smiling, but upon which I detected at times a fleeting expression of scorn.

But he observed none of the sartorial vagaries of the traditional poet. In fact, he wore black broadcloth, well cut, well fitted, well pressed.

He was always gay and friendly in company and wholly without affectations or mannerisms, a delightful talker, and as popular with men as with women.

Life offered him a brimming cup and when he had drained it he found the dregs too bitter, and on November 18, 1926, he drank of another cup and was found writhing in death throes on his bed in the Bohemian Club. Genius oft carries a curse about its neck.

Whether time will give him a place among the mortals or not, his long dramatic poems are enchanting to read and it is to be hoped that one of these days, when the war god is amusing himself on some other planet, some New York or Boston publisher will take over from Harry Robertson the copyrights of Wine of Wizardry, The Testimony of the Suns, The House of Orchids, and Lilith and give them to another generation.

The Prosaic Life of the Poet

George Sterling was educated at private and public schools on Long Island and at St. Charles College, Ellicott City, Maryland. We have no notes from him on his school days, nor do we have many indications of his private thoughts. On February 7, 1896, George Sterling married Carrie Rand. His precarious financial situation was greatly aided by his uncle, Frank C. Havens, of Oakland. George Sterling served as secretary to his uncle from 1898 to 1908.

Meanwhile, he had begun his serious poetical endeavor. In 1903, he published The Testimony of the Suns and Other Poems, and in 1908, he published A Wine of Wizardry and Other Poems.

There is little indication that George Sterling’s poems were taken very seriously by the people around the San Francisco Bay. They were reviewed in the local newspapers, but nothing much was made of them. Other volumes appeared: The House of Orchids and Other Poems in 1911, and Beyond the Breakers and Other Poems in 1914.

Thereupon a certain amount of fame did come to George Sterling. He was asked to write the official Exposition Ode in 1915 and he gradually became known as the local poet laureate.

By this time, George Sterling had become greatly influenced by Ambrose Bierce (1842–1914?), the sharp and often savage satirist of San Francisco, who lampooned the frivolities of the day at every chance. Bierce took a fatherly interest in George Sterling. He showed the same sort of solicitous regard for Jack London (1876–1916), whose adventurous life as sailor, tramp, and gold-miner, fascinated George Sterling. The three friends—Bierce, London, and Sterling—were often together at the Bohemian Club in San Francisco, and they frequently spent long weekends at the Bohemian Grove on the Russian River, in addition to the regular two-week encampment each summer. Jack London was successful with his brilliant novels such as The Call of the Wild (1903), John Barleycorn (1913), The Mutiny of the Elsinore (1914), and The Little Lady of the Big House (1916).

George Sterling was profoundly distressed by the still unexplained fate of Ambrose Bierce in Mexico. It is not known how he reached his end, but it is assumed that he was killed by revolutionaries when he disappeared there sometime in 1913.

Jack London, in spite of his flamboyance and great success as a writer, was a moody and often discouraged person. His tremendous vigor impressed George Sterling, but there also was a tragic side to Jack London. His death is still not clear. It may have been suicide, but again it may not have been. He was busy building his rough stone home at Glen Ellen in the Sonoma Valley, and George Sterling often helped him when he could. Jack London’s wife, Charmian, was fond of George Sterling and often encouraged him.

George Sterling’s book of poems, A Wine of Wizardry, was published in 1908. Bierce’s influence is indicated in one of the poems, An Ode to Fancy, which took off from one of Bierce’s poetical comments:

When mountains were stained as with wine

By the dawning of Time, and as wine

Were the seas.

George Sterling wrote:

But evening now is come, and Fancy folds

Her splendid plumes, nor any longer holds

Adventurous quest o’er stained lands and seas—

Fled to a star above the sunset lees,

O’er onyx waters stilled by gorgeous oils

That toward the twilight reach emblazoned coils,

And I, albeit Merlin-sage hath said,

“A viper liketh in ye wine-cup redde,”

Gaze pensively upon the way she went,

Drink at her font, and smile as one content.

George Sterling had a rich visual imagery and used it effectively. That he could compose a rollicking verse is shown in his short twelve-line poem The Islands of the Blest:

In Carmel pines the summer wind

Sings like a distant sea.

Oh harks of green, your murmurs find

An echoing chord in me!

On Carmel shore the breakers moan

Like pines that breast a gale.

Oh whence, ye winds and billows flown

To cry your wordless tale?

Perchance thy crimson sunsets drown

In waters whence ye sped;

Perchance the sinking stars go down

To seek the Isles ye fled.

George Sterling, with Ambrose Bierce and Jack London, loved the Redwood Forest. They would sit and drink whiskey for hours under the sheltering arms of the great redwood trees in the Bohemian Grove and also on hikes through the Russian River country to such areas as the Armstrong Grove near Guerneville. George Sterling wrote, as part of one of his Grove plays, The Triumph of Bohemia:

O trees! so vast, so calm!

Softly ye lay

On heart and mind each day

The unpurchaseable balm.

Whiskey was the bane of the three friends. They seemed to have sought some degree of satisfaction from the frustrations which seemed always to beset them. They shared their frustrations in a brave effort to surmount them by raucous and often flamboyant behavior.

The Poet’s Struggle with Truth

One of the affluent San Franciscans who recognized the genius of the artistic Bohemians was James Duval Phelan (1861–1930). He was a bachelor, but lived happily for his friends. He had been mayor of the city at the beginning of the twentieth century and did much to promote the parks and playgrounds of the city as well as the library. He had much to do with the Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915, and it was probably his influence that gave George Sterling the opportunity to write the Exposition Ode. Actually, this effort of George Sterling was rather sophomoric, and he knew it.

James Phelan was United States Senator from California from 1915 to 1921. Nevertheless, during this period he continued to befriend George Sterling. When he left the Senate, Senator Phelan maintained a beautiful home at Montalvo, near San Francisco. To this beautiful estate, which has since become a center for artistic activity in the area, James Phelan would invite many of the artistic people of the community to spend time with him and to amuse each other by composing poetry and reading to each other, or by composing music. George Sterling was greatly impressed by the beauty and friendship expressed at Montalvo. After his death, the Oxford University Press published a number of his Poems to Vera in 1938. Some of these reflect the pleasure which Sterling and his friends had as guests of Senator Phelan:

How still the hour!

Remote

The day-moon seems to float,

Where quiet is, and forest-shadows fall,

Compassionate of all.

George Sterling had been entertained by many of the wealthy people in the San Francisco area. From these kindnesses shown to him came many of the poems published under the title, The House of Orchids. One of the poems therein was dedicated to Mrs. Joseph B. Coryell, after being at her home, Loyden, in June 1909:

And yet, o blossoms pure!

How marvelous the lore

Of your fragility and innocence—

This grace and wistfulness of helpless things

That ask no recompense!

Ye give the spirit wings,

For yours the beauty that is near to pain,

And stir the heart again

With visions of the flowers that abide—

Ah! Sweet

As when Love’s glances meet

Across the music, heard at eventide!

To George Sterling, there was a dichotomy between Beauty and Truth. Toward the latter part of his life, these two themes occur often. Somehow George Sterling seemed to be afraid of Truth. He embraced Beauty and wanted nothing to do with the search for Truth. In this respect, he exemplifies the frequent attitude of artists, musicians, and poets who do not understand what scientific endeavor is about, or how wonderful the truth can be, in a really artistic sense, when it is discovered. To George Sterling, Truth was always cold. This was the attitude he despised among the scientists who were his friends. And yet he respected Truth. He was afraid of it.

George Sterling’s obsession with the problem of Beauty and Truth reached its climax in the great Grove play, Truth, which was presented in the Bohemian Grove on the evening of Saturday, July 31, 1926. The final lines of this great dramatic poem express his feeling clearly:

O Truth, denied of men, take thy cold way

And leave to me this Beauty and this Love,

Though both be of illusion! Shadow of God,

Pass to thy snows, as I shall pass to dust.

To George Sterling, this was clearly the end. He had made up his mind. He would follow Beauty and Love, and let cold Truth go over the hill.

Poet’s End

Following the great success of the Grove play, Truth, George Sterling looked forward to increasing prospects of wide recognition as a serious poet. He heard from Henry Louis Mencken (1880–1956), the great Baltimore editor and satirist, and arranged for Mencken to come to San Francisco to visit him. He was looking forward to this meeting with moving anticipation.

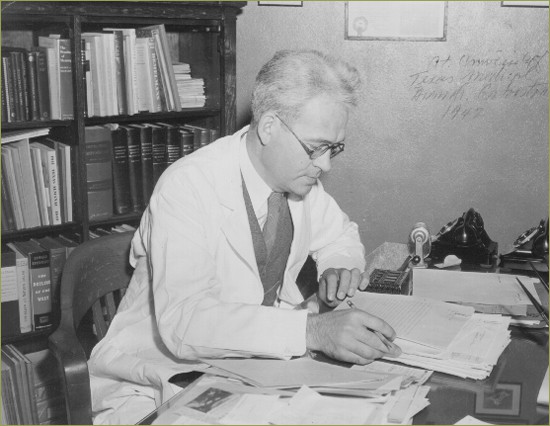

The end came suddenly. It has been described in vivid detail by Dr. Albert E. Larsen and his friend William Martin. Both of these young men had been befriended by George Sterling in the Bohemian Grove and at the Bohemian Club. Albert Larsen has prepared an account of the death of George Sterling, which is a straightforward eyewitness report.

“During the year 1926, as the shadows of Autumn descended, the curtain abruptly fell for one who modestly evaluated his lifetime contribution, which had evolved as a beautiful priceless legacy. I had recently achieved two great privileges: first—my degree as a Doctor of Medicine, and second—membership in the Bohemian Club. My good friend was William Martin, who became a member of the Bohemian Club at the same time as I did. We both had parts in George Sterling’s great Grove play, Truth. Actually, ‘Red’ Martin played the part of Truth, speaking no lines, but walking with great dignity up to the top of the hill as the lights on the play died out.

On Saturday evening, November 18, 1926, ‘Red’ Martin and I were on our way to attend a college dance. We decided to stop by the Club for a pleasant Saturday evening respite. We were delighted to find ourselves in company with the sole occupant of the Cartoon Room, our revered Club poet laureate, George Sterling.

Very quickly we realized that we were in the presence of a very disturbed individual, who welcomed company in pondering a momentous problem. On the following Tuesday, he had invited the great but caustic critic of the day, to a luncheon, and expected to be host to Henry Louis Mencken. What would be the reaction of this highly respected authority to the works of one who had striven so hard but, in his own estimation, had produced too little? When he learned of my newly adopted profession, he insisted on going to his room and bringing me the original copy of his latest completed work, The Pathfinder, which he felt was appropriately related to the problems of a young medical student. The conversation waxed excitedly and we promptly accepted an invitation to join in the luncheon party. We were enthralled with the prospect of dining with these two distinguished gentlemen. I was to read the manuscript of The Pathfinder and return the precious document at the luncheon.

As time wore on, with libations in the Cartoon Room, the intensity of George Sterling’s struggle with the immediate problem became more apparent. He yawned, seemed to be sleepy and distracted. Suddenly, he reached into his pocket, and dramatically brandished a vial—’Here you witness the end of George Sterling!’—and he now was in a state of complete collapse. We stretched him on a nearby couch to rest and sleep while we departed for our engagement.

Later, we were informed that he was carried to his room by the attendants, coached by Fong, the ancient Chinese factotum of the Cartoon Room. As George Sterling was being taken to his room, he uttered a deep sigh, followed by a burp, the last utterance of George Sterling. It is said that Fong expected George Sterling to be up and around the next day as usual, but it seems more likely that the burp was George Sterling’s last critique of his own efforts.

The prophecy of the vial came true, and there was no luncheon party. We never had the privilege of watching George Sterling and the great Mencken talking together. The manuscript of The Pathfinder is in the Bohemian Club Library. Certainly it should be examined by some competent critic and published if it is at all meritorious.”

George Sterling’s end created a considerable sensation. It is not clear what poison the vial contained, but it may have been potassium cyanide. If it was, George Sterling certainly took a large enough dose to have caused death. It seems that no postmortem examination was held. It may have been that the vial contained a solution of morphine sulfate, which simply would have put George Sterling to sleep, and given his restless spirit the peace and contentment it always sought.

George Sterling’s long struggle with Beauty and Truth is recorded in his verses so entitled:

Between the shadowy land and voiceless sea,

They met by twilight on the sterile coast.

Said Beauty: “I am of eternity.

Bow down to me!” Said Truth: “You are but ghost.”

And Beauty like a silver mist took flight,

And heard far off the sorrow of Time’s laughter.

Going she wept, with tears of bitter light,

And on her paths great pearls were found long after.

“See now!” cried Truth, “Her feet have left no trace!”

And at a pool abandoned by the tide

Knelt down to see the marvel of his face,

To find stars mirrored there and naught beside.

Sterling was willing to go with Beauty, and to leave Truth behind.

L’Envoi

One can perhaps be pardoned for attempting to eulogize George Sterling in a manner that he might have appreciated:

How few the poets who have known the Muse,

Or dreamed her name;

Who loved and feared her, Mother, Daughter, Bride,

The three the same!

White Goddess! Slender, face so pale, her lips

As blood so red;

With eyes a burning blue, and raven hair

Draped from her head:

Brave Man! With Eagles, Orchids, and Wizard’s Wine

You tracked her down!

Her Truth you found not worth the friendships

Which became your crown.

As one of the many amazing surprises of the past decade, poetry is again becoming fashionable. Poets speak with vigor on matters of immediate social concern, and they also attempt to hold to those ideals of Beauty and Love which so intrigued George Sterling. Some of our current poets are even beginning to understand that scientific endeavor, the search in itself for Truth, has poetical meaning. George Sterling was simply ahead of his time. When he was at his prime, before and after World War I, serious poetry was not in fashion. It is true that some of the war poems hit responsive notes, but they were part of the emotional impact of the war itself. George Sterling’s poetical interest was far deeper, and was in the long tradition of devotion to the Muse, ever concerned with Beauty and Love and disdaining the cold unpleasant reality of Truth.